- Home

- Eric Blehm

Legend

Legend Read online

Copyright © 2015 by Eric Blehm

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Broadway Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Broadway Books and its logo, B D W Y are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, in 2015.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 9780804139519

Ebook ISBN 9780804139526

Map on this page by Joe LeMonnier

Maps on this page, this page, and this page by Chris Adams, Rocketman Creative

Cover design: Chris Brand

Cover photograph: Larry Burrows/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

This page photograph by Florian Stern/Gallery Stock

a_rh_4.1_c0_r3

THE ANTIDOTE FOR FIFTY ENEMIES IS ONE FRIEND.

–ARISTOTLE

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Key Military Personnel for the May 2 Mission

Map

Prologue

Chapter 1: Street Kid from Cuero

2: “Look Sharp, Be Sharp, Go Army!”

3: The Darkest White

4: Green Beret

5: The Secret War

6: Anatomy of a Mission

7: Welcome to Detachment B-56

8: Over the Fence

9: The Launch

10: As Bad As It Gets

Photo Insert 1

11: Daniel Boone Tactical Emergency

12: If Someone Needs Help…

13: Last Chance

14: Deliverance

Photo Insert 2

15: Mettle for Medal

Epilogue

Dedication

Research and Acknowledgments

Also by Eric Blehm

KEY MILITARY PERSONNEL FOR THE MAY 2 MISSION

Military Assistance Command Vietnam,

Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG)

PROJECT SIGMA, DETACHMENT B-56

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Drake, Commander

First Lieutenant Fred Jones, Launch Officer

Captain Robin Tornow, U.S. Air Force Forward Air Controller (FAC)

PROJECT SIGMA, DETACHMENT B-56 RECON TEAM

Sergeant First Class Leroy Wright, Team Leader

Staff Sergeant Lloyd Mousseau, Assistant Team Leader

Specialist 4 Brian O’Connor, Radioman

Tuan, CIDG Interpreter

Bao, CIDG Point Man

Chien, CIDG Grenadier

CIDG Rifleman

CIDG Rifleman

CIDG Rifleman

CIDG Rifleman

CIDG Ammo Bearer

CIDG Ammo Bearer

214TH COMBAT AVIATION BATTALION (CAB),

12TH COMBAT AVIATION GROUP, 1ST AVIATION BRIGADE

240th Assault Helicopter Company

Major Jesse James, Commander

2ND PLATOON GREYHOUND SLICKS

AC = pilot/aircraft commander, left seat

CP = copilot, right seat

CC = crew chief/left-door gunner

DG = right-door gunner

BM = bellyman

Command and Control (C&C)

Major Jesse James, AC

First Lieutenant Alan Yurman (leader of 2nd Platoon), CP

Unknown, CC

Unknown, DG

First Lieutenant Fred Jones, Detachment B-56 Mission Launch Officer

Special Forces Major (name unknown), Detachment B-56 Observer

Greyhound One* (primary/lead)

Warrant Officer Larry McKibben, AC

Warrant Officer William Fernan, CP

Specialist 4 Dan Christensen, CC

Specialist 4 Nelson Fournier, DG

Staff Sergeant Roy Benavidez, BM

Greyhound Two (primary/wingman)

Warrant Officer Jerry Ewing, AC

First Lieutenant Bob Portman, CP

Specialist 5 Paul Tagliaferri, CC

Unknown, DG

Greyhound Three (reserve/lead)

Warrant Officer Roger Waggie, AC

Warrant Officer David Hoffman, CP

Specialist 4 Michael Craig, CC

Unknown, DG

Unknown, BM

Greyhound Three (second crew)

Warrant Officer Roger Waggie, AC

Warrant Officer David Hoffman, CP

Warrant Officer William Darling, CC

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Thomas Smith, DG

Staff Sergeant Ron Sammons, BM

Greyhound Four (reserve/wingman)

Warrant Officer William Armstrong, AC

Warrant Officer James Fussell, CP

Specialist 4 Gary Land, CC

Specialist 4 Robert Wessel, DG

Specialist 5 James Calvey, BM

3RD PLATOON MAD DOG GUNSHIPS

AC = aircraft commander/pilot, right seat/rockets

CP = copilot, left seat/miniguns

CC = crew chief/left-door gunner

DG = right-door gunner

Mad Dog One (first fire team/lead)

Chief Warrant Officer 2 William Curry, AC

Chief Warrant Officer 1 David Brown, CP

Sergeant First Class Pete Jones, CC

“Swisher,” DG

Mad Dog Two (first fire team/wingman)

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Michael Grant, AC

Chief Warrant Officer 1 Ron Radke, CP

Specialist 4 Steven Hastings, CC

Specialist 4 Donald Fowler, DG

Mad Dog Three (second fire team/lead)

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Louis Wilson, AC

Warrant Officer Jesse Naul, CP

Specialist 5 Paul LaChance, CC

Specialist 4 Jeff Colman, DG

Mad Dog Four (second fire team/wingman)

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Gary Whitaker, AC

Warrant Officer Cook, CP

Specialist 5 Pete Gailis, CC

Specialist 4 Danny Clark, DG

Mad Dog Five (emergency backup gunship, flown from Bearcat for extraction)

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Don Brenner, AC

First Lieutenant Rick Adams, CP

Specialist 4 John White, CC

Unknown, DG

* * *

* All helicopter numbers have been changed for clarity.

PROLOGUE

THIS STORY BEGINS in a U.S. government–issued body bag.

The date was May 2, 1968; the location, Loc Ninh Special Forces camp near the Cambodian border in South Vietnam. Inside the zippered tomb lay a stocky, five-foot-six-inch U.S. Army Green Beret staff sergeant named Roy Benavidez. Earlier that day he had jumped from a hovering helicopter, then ran through withering enemy gunfire to reach what remained of an American-led twelve-man Special Forces team surrounded by hundreds of North Vietnamese Army soldiers.

A few strides into his heroic dash, a bullet passed through his leg and knocked him off his feet. Determined to reach his comrades, he rose and continued his sprint, zigzagging through enemy fire for almost seventy-fiv

e yards before he went down again, this time from the explosion of a near-miss rocket-propelled grenade. Ignoring both the bullet and shrapnel wounds, he crawled the remaining few yards into the beleaguered team’s perimeter, took control, provided medical aid, and positioned the remaining men to fight back the endless waves of attacking NVA while he called in dangerously close air support.

For the next several hours, Benavidez saved the lives of eight men during fierce, at times hand-to-hand combat before allowing himself to be the last man pulled into a helicopter that had finally made it to the ground amidst the relentless onslaught. There he collapsed motionless, atop a pile of wounded and dying men. His body—a torn-up canvas of bullet holes, shrapnel wounds, bayonet lacerations, punctures, burns, and bruises—pasinted a bloody portrait of his valor that day.

—

FOR NEARLY a decade his story, and the story of the May 2 battle, remained untold. That was until Fred Barbee, a newspaper publisher from Benavidez’s hometown of El Campo, Texas, got wind of it and ran a cover story in the El Campo Leader-News on February 22, 1978. The intent of his article was twofold: to honor Benavidez by recounting his heroics and to berate the Senior Army Decorations Board for its staunch refusal to bestow upon Benavidez what Barbee believed was a long-overdue and unfairly denied Congressional Medal of Honor.

Barbee wanted to know what the holdup was. His tireless research elicited few answers from the Decorations Board, whose anonymous members, he quickly learned, answered to no one—not congressional representatives, not colonels (two of whom had lobbied for Sergeant Benavidez), and certainly not a small-town newspaper publisher.

But Barbee wouldn’t let it go. He was perplexed when the board cited “no new evidence” as its most recent reason for denying the medal, when in fact there was plenty of new evidence. Topping the list was an updated statement written by Benavidez’s commanding officer, citing previously unknown facts that corroborated the sergeant’s legendary actions. There was also testimony from the helicopter pilots and aircrews who witnessed the battle from the air or listened in on the radio as events transpired. According to the board, although these accounts were compelling, there was no eyewitness testimony from anybody on the ground. This criterion seemed impossible to meet; almost nobody on the ground May 2 had survived either that day or the war. The few who had were off the grid, having either become expatriates or burned their uniforms and melted into an American populace that more often than not had shamed them for their service in Vietnam.

“What, then, happened on that awful day…in the Republic of Vietnam?” Barbee questioned in his article. “Or, perhaps this particular action on May 2, 1968, actually took place outside the boundaries of Vietnam, perhaps in an area where U.S. forces were not supposed to be, perhaps that is the reason for the continuing runaroundnn….”

—

THE ASSOCIATED Press picked up Barbee’s article, and it circulated into some of the American news sections of international papers. By July of 1980, it had traveled halfway around the world to the South Pacific, finding its way into the hands of a retired Green Beret and Vietnam veteran who was living in Fiji with his wife and two young children.

Brian O’Connor immediately recognized the date in the article, May 2, 1968; the hours-long battle was his worst, most horrific memory from what was known as “the secret war.” He remembered being under a pile of bodies on a helicopter, slippery with blood and suffocating. Now, as he read the story, O’Connor was appalled to learn that Benavidez had never received the Medal of Honor. He knew he would have to revisit and recount his memory of the battle—in detail. He owed it to the man who had, against all odds, saved his life.

Determined to set the record straight, O’Connor dated a sheet of paper July 24, 1980, and addressed it to the Army Decorations Board:

“This statement,” O’Connor wrote, “on the events that happened on 2 May 1968 is given as evidence to assist the decision made on awarding the Congressional Medal of Honor to Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez. Because of the classified nature of the mission, some important details will be left out which should not in any way affect the outcome of the award.”

Page after page, the darkness flowed from his pen as O’Connor relived the nightmarish day. From the insertion of his twelve-man team deep behind enemy lines to the desperate hours when they were surrounded and vastly outnumbered by what many estimated was a battalion or more of well-armed North Vietnamese Army soldiers. He pieced together the torn and sometimes blurry snapshots from his memory, recounting the deaths of his teammates one by one, as well as the several helicopter rescue attempts beaten back by a determined enemy that was on the verge of overrunning their position:

The interpreter, who now had his arm hanging on to the shoulder by a hunk of muscle and skin, tugged at me to say the ATL [assistant team leader] wanted me. Firing and rolling on my side, I saw the ATL on his emergency radio and I nodded my head and the ATL hollered to me “ammo—ammo—grenades.” Stripping the two dead CIDG [Civilian Irregular Defense Group, the South Vietnamese Special Forces] of their ammo and grenades, I moved a meter or two, where I threw the clips and grenades to a CIDG, who in turn threw them to the ATL. During the minute or two of calm, the interpreter and I patched our wounds, injected morphine syrettes, tied off his arm with a tourniquet, and ran an IV of serum of albumin in my arm for blood loss…while the one remaining CIDG observed for enemy movement. I looked over to the ATL, and they were doing about the same thing…. We had another few seconds of silence and the ATL shouted, “they’re coming in.” I figured a final assault to overrun us and we prepared for the worst…. I caught a burst of auto fire in the abdomen and the radio was shot out. I was put out of commission and just laid behind [a] body firing at the NVA in the open field until the ammo ran out….

I was ready to die.

1

STREET KID FROM CUERO

“AYEEEEE!” THE BOY soldier shouted as he charged forward and jumped into the void. His battle cry was muffled when he landed in the mountain of seeds—bits of cotton still attached—that were piled high on the floor of the huge tin warehouse near his neighborhood in Cuero, Texas.

It was the fall of 1942, and sneaking into the local cotton warehouse and jumping from its loft into the remains of the recent harvest was a favorite pastime for seven-year-old Raul “Roy” Perez Benavidez. His inspiration was the local theater, where he’d watched newsreels of American paratroopers in World War II jumping one after another from an airplane thousands of feet above the ground. While the airborne soldiers drifted down beneath their silk parachutes, the narrator told of the adventurous lives of the “Battalions in the sky! Specially trained for fighting in the jungle—the kind of wilderness in which the Japs have got to be whupped in the South Pacific!” And then Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president of the United States, filled the screen. He sat at his desk and spoke to the forces fighting for freedom overseas—and to movie house audiences that included young Roy Benavidez in Cuero, Texas, who had paid the same nine cents for admission as the kids in the good seats but was upstairs in the segregated balcony, where clearly posted signs directed him and the rest of the “Mexicans and Negroes” to sit.

But when the lights went off and the screen lit up, Roy forgot about his lot in life—the personal battles, the fears, and how he’d earned those nine cents—and reveled in every minute of the fantasy. He imagined he was right there alongside the troops he was watching on screen, M1 rifle in hand, assaulting an enemy position on a distant shore.

“You young Americans today,” FDR said, staring into Roy’s eyes, “are conducting yourselves in a manner that is worthy of the highest, proudest traditions of our nation. No pilgrims who landed on the uncharted New England coast, no pioneers who forced their way through the trackless wilderness showed greater fortitude, or greater determination, than you are showing now!”

—

ROY WAS three years old when he moved

into Cuero with his mother, Teresa, and two-year-old brother, Rogelio, “Roger,” during the second week of November 1938. Just a few days earlier his father, Salvador Benavidez—a sharecropper and a vaquero (cowboy) on the nearby Wallace Ranch—succumbed to tuberculosis. Roy had been born on that ranch, brought into the world by a midwife in his parents’ bed. It was the same bed he had watched his father’s body lifted from and placed into a wooden box built by a neighbor. He would always remember the pounding of the hammer as the casket was nailed shut, then slid into the back of a pickup truck and put in the ground at the ranch’s tiny cemetery, beneath a wooden cross.

In Cuero, Teresa soon found work tending the household of a well-to-do doctor. A year later she married Pablo Chavez, who worked at the local cotton mill. After another year, Roy and Roger were joined by their baby sister, Lupe, who received all of their stepfather’s attention and most of their mother’s. His stepfather wasn’t cruel, just inattentive, offering little guidance to or affection for the two boys. They did, however, have plenty of freedom.

Situated on a branch of the Chisholm Trail, Cuero had been a frontier town where cowboys once congregated while driving their cattle from the southern plains to markets in the north. There were more automobiles than horses on the streets Roy explored, but the spirit of the Western town remained. Six-year-old Roy would observe a steady stream of men coming in and out of the “houses” strategically placed near the swinging doors of saloons located, it seemed, on every corner. He wanted to see what was going on inside but was always shooed away by the women wearing bright-red lipstick.

With its population of 4,700, Cuero was a thriving hub of business for the ranching, farming, rodeo, and agricultural industries. Roy was just another of the anonymous Mexican street kids who, charged with contributing to their family coffers, provided well-to-do farmers, ranchers, and businessmen labor for odd jobs: a dime shine for their shoes, a five-cent taco for their bellies, and the occasional philanthropic entertainment. Such shows would begin when a man wearing a pressed suit or fancy cowboy boots would gather some friends, then toss a handful of coins onto a street corner where the children were looking for work or selling their wares.

Legend

Legend The Last Season

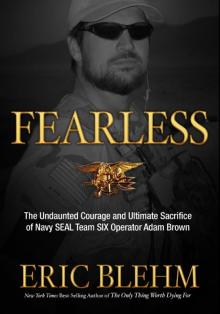

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For