- Home

- Eric Blehm

The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For Read online

The Only Thing Worth Dying For

How Eleven Green Berets Forged a New Afghanistan

Eric Blehm

This story is dedicated to the men and women of the coalition forces who have fought in Afghanistan, and to their families and loved ones, many of whom have come to realize that not all battles end with the war.

Ten good soldiers, wisely led, will beat a hundred without a head.

—Euripides

Contents

Epigraph

Prologue

1 A Most Dangerous Mission

2 The Quiet Professionals

3 To War

4 The Soldier and the Statesman

5 The Taliban Patrol

6 The Battle of Tarin Kowt

7 Credibility

Photographic Insert

8 Madness

9 Death on the Horizon

10 The Ruins

11 The Thirteenth Sortie

12 Futility

13 Rescue at Shawali Kowt

14 Worth Dying For

Epilogue

Map of Tarin Kowt

Map of Shawali Kowt

Acknowledgments

Selected Bibliography

Notes

About the Author

Other Books by Eric Blehm

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

I met Hamid Karzai, the president of Afghanistan, at the Barclay Hotel in midtown Manhattan on September 23, 2008, when he was approaching the end of his five-year term as the country’s first democratically elected leader. Since 1700, twenty-five of the twenty-nine rulers of Afghanistan had been dethroned, exiled, imprisoned, hanged, or assassinated.1 That Karzai had survived multiple assassination attempts since taking office was a feat in itself. Even more remarkable, however, was the journey that had brought him to this presidency.

He greeted me in perfect English with a British accent, shook my hand firmly, and ushered me across the elegant room of his suite. Though it was Ramadan, when Muslims fast from dawn to sunset, he offered me cookies and coffee or tea, which I declined out of respect for his religion. Sitting opposite the president in a cushioned armchair, I handed him a stack of photographs. As he held them in his palms, he stared intently at the one on top: eleven American soldiers grouped tightly around him on a sandy hillside in southern Afghanistan. A smile spread over his face, and he began to nod as he flipped through the pictures chronicling the mission that had changed the course of history.

For nearly two years, I had been trying to interview Karzai so that he could confirm crucial details of his rise to power during the early days of the Global War on Terror, a war that Karzai and his staff—who had joined us in the room to hear their president tell his stories—called by another name: the Liberation. He transported us to the mud-walled safe houses of his insurgency, where, lit by kerosene lanterns, turbaned freedom fighters with AK-47s planned strategy with U.S. Special Forces soldiers wearing camouflage. He led me through the photos, which I had placed in chronological order, taking us back to October, November, and December 2001.

I was concerned that he might not be able to recall details about the men who had sacrificed so much for both America and Afghanistan in carrying out one of the war’s most dangerous and secretive missions. I wondered whether all that he had experienced in the ensuing years had erased or distorted his memories.

Then he held up a photo to his staff and pointed to an American soldier. “Had there been anybody else, things would have gone terribly wrong,” he said. A mournful tone now entered his voice. “Oh, some good men…”

“Very sad,” he said about the next photo. “This is perhaps a day or two before he died.” Looking closely at the following photo, he said, “This man is dead. And this man—he is also dead. And this man.”

“When?” I asked. “Do you remember the date they died?”

“Of course,” he answered. “How could I forget?”

The following is a true narrative account of modern unconventional warfare as recalled by the men who were there. Some names have been changed to respect the privacy of the individuals.

CHAPTER ONE

A Most Dangerous Mission

* * *

[H]e knew from experience how simple it was to move behind the enemy lines…. It was as simple to move behind them as it was to cross through them, if you had a good guide.

—Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls

* * *

Late on the night of Tuesday, November 13, 2001, Hamid Karzai and his military adviser, U.S. Special Forces Captain Jason Amerine, walked briskly down a deserted road near their safe house in the Jacobabad District of Sindh Province, Pakistan. For Amerine, it felt almost as if they were walking along a country road stateside, the adjacent unplanted fields softly illuminated by starlight. In the distance, a half mile to the west, a dull glow marked more densely populated civilization, but here they were relatively isolated.

Karzai was unarmed and wearing the traditional Afghan shalwar kameez,* and his poise and flowing arm motions marked him as an orator. Tall and thin, Amerine had an M9 pistol tucked into the belt of his camouflage uniform. Above a coarse brown beard, his alert eyes never stopped scanning the dark fields while he and Karzai spoke in hushed tones.

“I just received confirmation,” said Amerine. “Tomorrow is the night—have you heard any news from the tribal leaders in Uruzgan?”

“Yes,” said Karzai. “I followed up with one of the local chiefs in War Jan. If the location we decided upon is safe, if no Taliban patrols are nearby, the signal fires will be lit as planned.”

“Your men are ready?”

“They are—word has spread about Kabul. The Pashtun are ready to join the fight.”

Earlier that day, allied U.S. and Northern Alliance resistance forces had liberated Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, from the Taliban. That was in the north; in the south, the home of the majority Pashtun ethnic group and the birthplace of the Taliban movement, things weren’t going so well. Neither the CIA nor the U.S. military had been able to establish a presence, and there was no organized resistance like the Northern Alliance. The few Afghans who dared to oppose the Taliban had been imprisoned or killed.

For four weeks beginning in early October, Karzai had traveled the region unarmed, trying to persuade leaders throughout the Pashtun tribal belt to rise up against the Taliban. The CIA considered this undertaking so dangerous that it refused to put any men on the ground with Karzai, limiting its involvement to giving him a satellite phone so that a case officer could monitor his progress. By the end of October, Karzai and a small group of followers had been pursued by the Taliban into the mountains of Afghanistan’s Uruzgan Province. Using the phone, he called for help on November 3 and was rescued by a helicopter-borne team of Navy SEALs.

Though he’d been chased out of Afghanistan, Karzai told the CIA that the Pashtun in the south were ready to rise up—if he returned with American soldiers who could organize and train them into a viable fighting force.

Only a few individuals were supposed to know that Karzai was now in Pakistan, so it had shocked and angered both Karzai and Amerine when U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld disclosed Karzai’s whereabouts to the media during a Defense Department press briefing earlier that week. Rumsfeld recanted what he called his “mistake” a couple of hours after he made it, telling the press that while Karzai was being assisted by U.S. Special Forces (Green Berets), he was somewhere in Afghanistan, not in Pakistan.

Amerine and Karzai feared that the Pashtun would interpret the news that Karzai was in Pakistan as a sign of weakness. Every village elder, Taliban deserter, and f

armer who might otherwise support him could withdraw their backing or, even worse, turn on Karzai. In order to maintain credibility within the Pashtun tribal belt, he and Amerine would return to Afghanistan on the most dangerous and politically important mission thus far of Operation Enduring Freedom.*

Now, walking down the center of the gravel road, Karzai and Amerine were reviewing the plan for the following night’s mission, when the eleven members of Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 574, Amerine’s Special Forces “A-team,” would be the first American team to infiltrate into southern Afghanistan. There, they would link up with the Pashtun tribal leaders and villagers who had promised Karzai allegiance.

The purpose of this mission was twofold: destroy the Taliban in the important southern city of Kandahar, where they were expected to regroup after the fall of Kabul; and unite the southern Pashtun tribe with the northern Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras. The Northern Alliance was on course to topple the Taliban, so unless the Pashtun joined the fight, they would be frozen out of the government that would rule after the Taliban. If this happened, Karzai was convinced that Afghanistan would descend into another devastating civil war.

Headlights appeared behind the two men, and Amerine quickly ushered Karzai to the side as a large flatbed truck passed by.

“There is something else, Jason,” said Karzai, falling back into stride behind the truck’s taillights. “Just an hour ago I received a call that my supporters in the town of Tarin Kowt are discussing an uprising to overthrow the provincial governor in Uruzgan Province.”

“It’s too early,” Amerine said. “If they succeed, they won’t be able to hold the town. The Taliban will slaughter them and fortify their position, which will make our job all the more difficult when we move on Tarin Kowt.”

“I will call the tribal leaders when we return,” said Karzai.

Nodding his approval, Amerine reflected back to the week before, when the name Hamid Karzai had meant little more than an obscure warlord. “You can’t trust anything these guys say,” Amerine’s team sergeant, JD, had warned him. “They will smile and tell you exactly what you want to hear—but don’t trust them to cover our backs.” Amerine had been wary, and rightly so. As a thirty-year-old captain, he alone would decide whether Karzai’s questionable southern rebellion against the Taliban was worth gambling the lives of American soldiers. His soldiers.

Karzai was not the warlord Amerine had expected. To the contrary, he was dignified, cultured, gentle. Still, Amerine had thought, that doesn’t mean he’s trustworthy. Nine days before, on the first of their nighttime walks, Karzai had posed some awkward questions: “Who will govern Afghanistan after the terrorists and the Taliban are defeated? What are the U.S. government’s long-term plans for Afghanistan?”

Other than hunting down the terrorists responsible for the attacks on September 11, 2001, Amerine suspected that the United States had no comprehensive plan, military or otherwise. He wasn’t obligated to answer Karzai’s questions, but he did want to build a foundation of trust with him. “I don’t know,” he had admitted.

“My fear,” Karzai replied, “is that the warlord generals of the Northern Alliance will use the momentum they’ve gained working with your American forces in the north, and take over the government as they move through the country reclaiming their cities.”

He explained that the September 9, 2001, assassination of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic leader of the Northern Alliance, had spurred a bloodless battle among those warlords. The generals had managed to settle their differences—at least temporarily—enough to unite with the United States against the Taliban and the terrorists. “But even if one warlord rises to the top,” said Karzai, “a much bigger problem will result.” The majority ethnic group—the Pashtun in the south—would “never be ruled by a minority ethnic group leader from the north who takes control,” he said. “Especially after the atrocities committed by both sides during the civil war.* A new civil war would be inevitable. Afghanistan would be ripe once again for the next Taliban or al-Qaeda.”

Please don’t tell me you want the power, Amerine had thought, anticipating the age-old solution to problems raised by a politician: the politician himself. Aloud, he’d asked, “What do you think would be best for Afghanistan? Who would be the right man for the job?”

“The best person for the job,” Karzai had said, “is not for me to decide. That is for the Afghan people to consider. I want to see the people voting, as in the United States. My dream is to see a Loya Jirga—a grand council where the tribal leaders set down their guns and talk. For years I have been talking about this. Nobody has listened.”

By now, on the eve of the team’s mission, Amerine had determined—over the course of several walks the past nine days—that Karzai was neither a warlord nor a politician. Indeed, he seemed to be a visionary idealist, a gallant statesman whose quest in Afghanistan bordered on quixotic.

Amerine liked the man. More important, he felt he could trust him.

The following morning, the safe house was abuzz with activity as ODA 574 from the Army’s 5th Special Forces Group prepared for that night’s infiltration into Afghanistan.

The eleven-man A-team had gathered in their meeting room in the safe house, dressed in a mix of desert camouflage pants, dark civilian fleece or down jackets over thermals, Vietnam War–era boonie hats, and baseball caps bearing such logos as Harley-Davidson and Boston Red Sox. As a sign of respect for the Afghan culture, none had shaved for the past month, starting before they had even left Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Amerine watched as his weapons sergeants, Ronnie, Mike, and Brent, laid out enormous piles of weaponry and ammo as well as two laser-targeting devices and began to discuss the distribution of their loads. The only non–Green Beret on the mission, an Air Force combat controller (CCT) named Alex, joined the communications sergeants, Dan and Wes, in making final checks on all radios, laptops, and batteries. Victor, the engineer responsible for the load plan, paced back and forth between the two groups of men and their piles, ready to re-weigh the equipment for the helicopters that would fly them in. Every passenger and every item they carried had to be weighed and logged. Assigned to the team at the last minute, Ken, the medic, was leaning up against a wall with the medical supplies organized in front of him, laying out small but ominous morphine injectors that he would issue to each man.

JD, the team sergeant and Amerine’s number two, and Mag, the intelligence sergeant and third in command, placidly observed the scene. They were veterans of the Gulf War and had seen all this before.

By noon, the eleven men had double-and triple-checked their gear. Each would carry an M4 carbine,* an M9 pistol, grenades, ammunition, food, water, minimal clothing in shades of desert camouflage, a midweight sleeping bag, and a waterproof jacket. Each man would also carry gear specific to his job—communications equipment, medical supplies, extra weapons—that added another fifty-plus pounds per pack. They had no body armor or helmets: for this unconventional warfare mission, the team would share the risk with the guerrillas they would lead. If Karzai’s followers did not have armor, neither would they.

The load was split between a bulging rucksack and a smaller, lighter “go-to-hell” pack of survival essentials, always kept on their bodies in case they had to jettison their rucksacks in a firefight or retreat. Together, the two packs weighed about 150 pounds (not including fifty pounds of radios, grenades, and ammo in their load-bearing vests, and a ten-to fifteen-pound loaded weapon), so heavy the men had to lie down on the ground to put on the shoulder straps, then roll over on all fours, and still needed help to stand up.

Extra team gear such as flares, computer equipment, and medical supplies for the indigenous population filled a half-dozen duffel bags that would be shuttled by vehicle or pack animal, both of which had been promised by Karzai.

An officer from Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) arrived to brief ODA 574, as well as the men from the Central Intelligence Agency who would be infiltrati

ng with them, on their flight and escape-and-recovery plans. As the officer spoke, Amerine felt an eerie connection to the three-man Jedburgh teams—considered the predecessors to both Special Forces soldiers and CIA agents—that had parachuted behind Nazi lines to assist the resistance fighters during World War II.1 Those teams had received similar briefings. How many made it back alive? Not many, thought Amerine.

The CIA team, led by a spook called Casper,2 sat beside Amerine’s men as the officer explained that they would be flown by AFSOC pilots from a nearby airstrip to a clandestine one near the Afghanistan border on two MH-53 Pave Lows,3 the Air Force’s heavy-lift helicopters. There they would board five smaller MH-60 Black Hawk helicopters—piloted by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR), which specializes in clandestine low-altitude night operations—for the flight into Afghanistan.

Shortly before 3 P.M., ODA 574 was loading gear onto a flatbed truck for transportation to the helicopters when Casper drove up with three men in a Humvee, parked, and approached Amerine, shaking his head. “Change in plans, skipper,” he said.

Here we go again, thought Amerine.

In the War on Terror, the CIA and Special Forces were working side by side, but with Special Forces running military operations, Amerine couldn’t determine exactly what the CIA’s role in Afghanistan would be. Casper’s agenda had at times intruded during the planning of the mission, even though Amerine had been told that he and his men were in charge of the insurgency.

Legend

Legend The Last Season

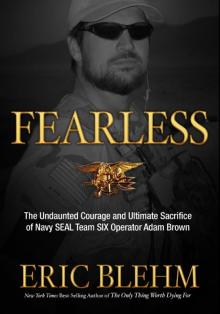

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For