- Home

- Eric Blehm

The Only Thing Worth Dying For Page 3

The Only Thing Worth Dying For Read online

Page 3

Although the flashlight continued to flicker in the distance, here they felt sheltered enough to try to orient themselves. Unfolding the map produced a crackle that was, in this silence, almost as disconcerting as gunfire. Jesus, Mag thought, might as well make some popcorn while we’re at it. But the flashlight didn’t waver.

Using their GPS, they figured out that their position was below the valley where the main group had landed. The Helmand River and its Taliban-patrolled villages were more than two miles to the west, at the base of the mountains. Only one and a half miles lay between them and the rest of the team to the east, but on terrain like this it might as well have been fifty. Their best course of action was to stay put, avoid detection, and pray that they could make radio contact by morning.

As Mike continued trying to radio the rest of the team, one thing was certain: Pashtun tribesmen didn’t normally travel around the mountains at night. Whoever was out there with that flashlight was not a goatherd looking for a lost kid.

CHAPTER TWO

The Quiet Professionals

* * *

It makes no difference what men think of war…. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him.

The ultimate trade awaiting the ultimate practitioner.

—Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

* * *

Two months earlier, on September 14, Captain Jason Amerine had been sitting in a hotel room in Almaty, Kazakhstan, writing in his journal, when his burly senior communications sergeant, Dan Petithory, knocked on the door. Dan was dressed casually in jeans, a T-shirt, and a Boston Red Sox baseball cap, but his normally jovial eyes were narrowed in an intense glare.

Amerine was immediately concerned—the last news Dan had delivered was that of the terrorist attacks on the United States three days before.

“Kazakhstan,” said Dan, entering the room. “Shit. We’re still only in Kazakhstan. I’m here a week now…waiting for a mission, getting softer.” He began to pace. “Every minute I stay in this room I get weaker, and every minute Osama squats in a cave, he gets stronger. Each time I look around, the walls move in a little tighter.” Dan threw a mock punch at a mirror.

Amerine laughed. He’d always admired the sergeant’s ability to ease a tense situation by quoting the perfect movie line. Dan’s spot-on impersonation of Martin Sheen’s opening monologue as Captain Willard in Apocalypse Now made light of the reality: The men of ODA 574 were restless, sequestered in this hotel killing time when all they really wanted to do was kill the terrorists responsible for the attacks on their homeland.

Picking up where Dan left off, Amerine said, “Everyone gets everything he wants. I wanted a mission, and for my sins they gave me one. Brought it up to me like room service. It was a real choice mission, and when it was over I’d never want another.”

“Not bad, sir,” Dan said with a chuckle. “You’ve got a Captain Willard thing going on without even trying. Anyway, your mission tonight is to get drunk with Colonel Asimov.”

For the previous year, ODA 574 had been teaching counterinsurgency tactics to Colonel Asimov’s airborne battalion, but during his five deployments to Kazakhstan during this time, Amerine had barely interacted with the high-ranking Kazakh army officer.

“No shit?” said Amerine.

“No shit, sir,” said Dan. “Meet in the lobby at eight P.M. He’s sending taxis for the whole team. Private dinner at some old KGB hangout…and sir? Don’t forget your liver.”

The aroma of savory beef-and-horse-meat stew wafted into the dimly lit dining room, where it mingled with plumes of cigarette smoke from the boisterous crowd. Dressed as civilians, the men of ODA 574 drew little attention as they followed a uniformed Kazakh officer through a doorway at the back of the restaurant.

In a private dining room at the top of a flight of wooden stairs, Colonel Asimov stood abruptly as the Americans entered, as did his twelve subordinates, whose blue-and-white-striped undershirts at the necks of their uniforms identified them as Kazakh paratroopers. The colonel was shorter than his men and markedly thin, with an emaciated, skull-like head. When he smiled, gold teeth glinted.

He waved Amerine to his side and beckoned the rest of the team to sit around the long table laden with traditional Kazakh and Russian dishes—flat bread, herring, and beet salad. Bottles of beer and soft drinks stood sweating at the center of the buffet, where they would remain. The Kazakhs assumed the Americans were off to war, and that called for vodka.

During the Cold War, as sworn enemies of the United States, the men in Asimov’s unit had fought the U.S.-backed Mujahideen in the Soviet war with Afghanistan.* Now, little more than a decade later, Asimov offered a toast: “To our enemies, who are now our allies.”

The men raised their glasses. The drinking began.

The Kazakhs quickly drained glass after glass of vodka. The Americans paced themselves, stalling as courses of food were delivered. When the colonel realized that they were nursing their drinks, he upped the number of toasts, shot after shot in honor of everything from John Wayne to the colonel’s dog. As Asimov extolled the greatness of both American and Kazakh airborne, ODA 574 began shuttling glasses to the adjacent bathroom, where they replaced the vodka with tap water.

At last, Asimov lit a foul-smelling cigarette and launched into a rambling speech recounting the Soviet–Afghan War. With a drunken slur, he spoke of the Afghans they had killed, the men he had lost in the slow defeat of the Soviet army, and the multitude of walking dead who had returned home. He ended with a solemn warning to ODA 574: “Do not trust the Afghans. Do not trust your friends. Do not trust anyone except your enemies.”

The colonel drained his vodka and set the tumbler upside down on the table. His dour expression turned into a grin.

“Time for bed for the young paratroopers,” he said, standing up and nodding toward Junior Weapons Sergeant Brent Fowler, who had considered it disrespectful to his host not to drink vodka with every toast and was now passed out in his chair.

Amerine followed Asimov outside to his waiting sedan. While his driver opened the back door of the car, the colonel gripped Amerine’s hand and looked him in the eye. “Captain Amerine,” he said, “I do not believe that anyone can win a war in Afghanistan. Just try to bring your men home alive.”

That same day at Fort Campbell, Kentucky,* Amerine’s company commander, Major Chris Miller, strode across the block belonging to 5th Special Forces Group.

In 2001, 5th Group was one of seven Special Forces groups in the U.S. military, each focused on a different geographic area of the globe with the sole purpose of supporting the fifty-four ODAs assigned to it. There are six ODAs—each led by a captain—to a company, led by a major; three companies to a battalion, led by a lieutenant colonel; and three battalions to a Special Forces group, led by a colonel. This bureaucracy serves one purpose: to provide support to the elite ODAs that do the actual fighting in order for them to accomplish their missions.

Thirty-five-year-old Miller had done his time as an ODA captain, and now, as much as he would have loved to parachute into Afghanistan and shoot Osama bin Laden in the face, his duty was to oversee and support his six Alpha Company ODAs. The only team of Miller’s not at Fort Campbell on 9/11 was ODA 574, and Amerine had been badgering his major since the terrorist attacks for information about the role Special Forces would play in the military response. Miller hoped to have something concrete for Amerine following the morning meeting with his boss, 3rd Battalion’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Queeg. Queeg wasn’t his real name, but Miller—and most of 5th Group—likened him to the eccentric, sometimes tyrannical Captain Queeg from Herman Wouk’s 1951 novel, The Caine Mutiny. Like the fictional Queeg, the commander was notorious for melodramatic speeches, angry outbursts, and being difficult to work with.

Since 9/11, Miller and the two other company commanders in 3rd Battalion had been attending three mandatory meetings a day—up from the usual one per week. At fi

rst, when Queeg had told them, “Hey, let’s not jump to conclusions; I’ve been through this kind of thing before,” Miller had exchanged looks with the two commanders. They were all thinking the same thing: How the hell has he been through something like this before?

At this morning’s meeting, Queeg had them hold hands as he led them in prayer, which was disturbingly out of character. The more he talked, the more he seemed to feel in control, but Miller got the distinct impression that he wasn’t.

Man, thought Miller, this guy does not have a clue what we’re fixin’ to do.

Shortly after the prayer, the commander of 5th Special Forces Group and Queeg’s boss, Colonel John Mulholland,1 strode into the room.

“I need to talk to Major Miller,” he said to Queeg. “Can I borrow him for a minute?”

Having taken command of 5th Group just two months earlier, Mulholland knew few of his men personally, but he had worked with Miller planning some classified missions over the previous two years and considered him a resourceful and reliable Green Beret.

The two stepped outside the office and faced each other in the empty hallway.

“Chris, I was just notified that they’re having a planning conference in Tampa at SOCCENT* starting this Monday,” Mulholland said. “I want you to go down there and get us into the fight.”

In Quetta, Pakistan, on September 15, Hamid Karzai was having tea with a group of close friends in a café near his home.

In 2001, the forty-three-year-old Afghan was unknown on the international stage.2 But in this café he was nobility, a direct descendant of Ahmad Shah, founder of the Durrani dynasty, which had ruled Afghanistan for more than two centuries. Hamid’s father, Abdul Ahad Karzai, had served in the Afghan parliament in the 1960s and had been the chief of the Popalzai, a distinguished subtribe of the Durrani clan, itself a part of the Pashtun ethnic group—the dominant majority in Afghanistan from which the Taliban arose.

The Afghan expatriates sipping tea with Karzai respected him, not only for his lineage but also because he had not used the privilege it afforded him as a shield from danger. During the Soviet occupation, Karzai’s five brothers and one sister had emigrated to Western countries while he finished his master’s degree in international relations and political science at India’s Himachal University. In 1983 he returned to Afghanistan, where his knowledge of English, French, Dari, Pashto, Persian, Urdu, and Hindi helped him to channel funds and weapons to the Mujahideen in their war with the Soviet Union.

After the Soviets retreated in February 1989, Karzai, then thirty-one, served the newly established Mujahideen government as deputy foreign minister. In that post, he watched helplessly as the rival factions of the Mujahideen dragged his beloved Afghanistan into a brutal civil war. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed in the lawlessness that plagued the country until a one-eyed former Mujahideen foot soldier named Mullah Muhammed Omar and his Taliban brought stability in the mid-1990s.

Omar’s Taliban movement was sparked by the rape and murder of two young boys at a checkpoint on a road outside Kandahar in June 1994.3 Mullah Omar, then the imam of a mosque in the Maiwand District west of Kandahar, led a band of armed students from his small madrassa to the checkpoint, where they killed the checkpoint commander and his men. He became a national hero, and his students of Islam, or Taliban, grew into an organized fighting unit. Composed overwhelmingly of ethnic Pashtun, mostly from the Durrani clan, the Taliban retaliated against brutality, extortion, and other injustices throughout the southern provinces of Helmand, Kandahar, and Uruzgan, and were hailed by Afghans for restoring a degree of safety they had not experienced in many years.

It was during this time that Hamid Karzai, who shared the movement’s early vision of peace and stability, joined the Taliban as a spokesman.

In November 1994, just five months after its inception and now backed by Pakistan, the Taliban took the city of Kandahar; within a few months, Mullah Omar controlled twelve provinces across southern Afghanistan. The country’s other twenty-two provinces were controlled by regional warlords, the majority belonging to the Northern Alliance, a coalition of minority tribes including Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras and backed by Russia, India, and Iran. In the ensuing two years, the Taliban moved north and in September 1996, Omar captured the capital city of Kabul. Though Kabul would remain Afghanistan’s official capital, the Taliban continued to rule from Kandahar, their spiritual home.

At first Karzai believed the Taliban leadership to be honest and honorable, but by 1996 he began to notice that their priority was shifting from Afghanistan’s welfare to maintaining political power. He suspected that Taliban policy was being heavily influenced by Pakistan and by Arab terrorist groups—including Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda network—that were permitted to operate freely in Afghanistan. Karzai also became increasingly wary of the Taliban’s fanatical interpretation of Islam. That year, he shunned the Taliban when he refused an appointment to become Afghanistan’s ambassador to the United Nations. As a result, he was no longer welcome in his own country, and he left to join his father in Quetta, Pakistan, where they began quietly to champion an anti-Taliban movement, petitioning foreign governments to intervene. Even though Hamid was not his eldest son, Abdul Ahad Karzai named him the heir to his position as chief of the Popalzai tribe—a decision uncontested by Hamid’s brothers, who had no political aspirations.

The younger Karzai visited the embassies of the United States, Great Britain, France, China, and other countries to warn of the suffering the Taliban was inflicting in Afghanistan and the growing number of terrorists using it as a base of operations. Over the next few years he became more vocal in his denunciations. These “dark years,” as he called them, were branded by gross human rights violations committed by the Taliban, which caused the international community to impose heavy-handed sanctions on the already oppressed Afghan people. When Taliban assassins gunned down the elder Karzai on his way home from a Quetta mosque in 1999, Hamid became chief of the Popalzai tribe and defiantly escorted his father’s body on an overland burial procession from Quetta to Kandahar.

On July 20, 2000, Karzai testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations about the terrorist organizations flourishing in Afghanistan. He warned that the Clinton administration’s response to the August 7, 1998, suicide car bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania—firing cruise missiles at terrorist training camps—was not enough. “Bombings or the threat of bombings,” he said, “will not remove terrorist bases from Afghanistan. Such actions will only add to the problems and prolong the suffering of our people and, worst of all, solidify the presence of terrorist groups. I call upon the international community, and particularly upon the government of the United States…. [T]he time to watch is over and the responsibility to act is long overdue.”

Karzai spent hour after hour in meetings with Western ambassadors and intelligence officers. If he could convey the severity of the looming threat posed by the terrorists the Taliban had welcomed into Afghanistan, he reasoned, perhaps the Western powers would help defeat them and, in the process, oust the Taliban. Karzai believed that the Afghan people would embrace a more moderate political and religious environment, such as the one before the Soviet occupation, when Afghanistan’s diverse factions each had a voice at the ruling Loya Jirga.

On September 11, 2001, Karzai was in Islamabad, Pakistan, preparing for meetings at Western embassies scheduled for the following day. The attack on the United States resulted in cancellation of those meetings and also conveyed, in a way that could not be ignored, the need for the regime change Karzai sought. In the days that followed, conversation among Karzai’s fellow Afghans at the café in Quetta turned to speculation about the U.S. response that was sure to come. Everyone knew that al-Qaeda operated training camps in Afghanistan—Karzai had been warning about it for years. He felt that the people of Afghanistan had had enough of the Taliban’s fanatical rule: the public executions, the closing of sch

ools, the mistreatment of women, the ban on music and games. Rather than wait for the United States to act, however, Karzai decided to launch his own insurgency.

“The time is right,” he told his friends. “Let us move back into Afghanistan. The eyes of the world are upon us.”

Armed with credentials and passwords, Major Chris Miller entered the Special Operations Command Central (SOCCENT) bunker—a shelter used by B-52 crews during the Cold War—at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida. Once past the entrance guards, he made his way underground through several cipher-locked doors to the office of Major Robert Kelley. It was Monday morning, September 17, and for the past six days, Kelley, who was SOCCENT’s chief of plans, had been attending the highest-level meetings to plan a military response to the terrorist attacks. Only a few people on the planet knew precisely what military options the United States was considering in the hours and days following 9/11, and Kelley was one of them.

Kelley looked up from his computer screen. “Chris!” he said, surprised to see his friend and fellow Green Beret in the doorway. “Who let you in here?”

“I cracked the codes on the cipher locks,” Miller joked. “Actually, Mulholland sent me over to make sure Fifth Group gets in the fight.”

Legend

Legend The Last Season

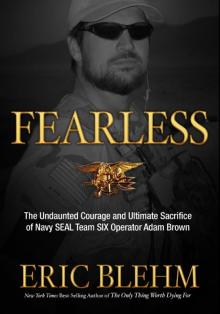

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For