- Home

- Eric Blehm

Legend Page 3

Legend Read online

Page 3

“Someday,” he told Roy, “someone will open a door to you, and you must be there saying, ‘Let me in.’ My future and yours will be in a different world than Grandfather Salvador’s. We will not give up our heritage, but we won’t let it hold us back either. We will be judged by the way we act and by the respect we earn in the community.”

As a bilingual barber and mechanic, Uncle Nicholas was an open ear for conversations from all walks of El Campo life, and when asked his opinion he always gave it straight. One afternoon two men—one Anglo and one Hispanic—got into a fender bender on the street outside the barbershop, where the sheriff was having a haircut. Without any witnesses, the sheriff had a difficult time getting to the bottom of the accident as the drivers yelled at each other in English and Spanish. Nicholas stepped in, heard both sides, translated the Spanish, and conferred with the sheriff, who then rendered the accident to be without fault.

And so, Nicholas “became known for resolving problems between the communities,” Roy said. “He didn’t do it with his hat in his hand and his eyes on the ground asking for favors, and he didn’t do it with threats. If our folks were wrong, he’d say so and stick to it. If the Anglo side was wrong, he’d talk sense until their ears fell off or they agreed, just as he sometimes preached to us.”

Soon after, a long-closed door at the Wharton County Sheriff’s Office swung open and Nicholas was invited in. He was offered a part-time job as a deputy—the first Hispanic deputy in the history of the county.

It was 1947. Roy was twelve when he and Gene accompanied Nicholas to pick up his new badge and sign some documents. At the station a deputy told Nicholas that he would have the right to arrest Hispanics and blacks, but not whites. If a situation warranted such an arrest, Nicholas would have to bring in another deputy.

“No,” Nicholas said. “If I wear this badge, then I will have the authority to arrest any person who breaks the law.”

The deputy shook his head. “That’s not going to fly, Nicholas.”

“Then,” said Nicholas, “I cannot accept the job.”

“I’m going to have to speak with the sheriff,” the deputy said.

Nicholas was called back to the station the following day. He came home with a badge—and the authority to arrest anybody who broke the law, regardless of the color of their skin.

—

ROY LEARNED just how serious his uncle was about fairness within the law when Deputy Benavidez was called upon to break up a brawl a few months into his new job, during a time when gangs were forming in El Campo and knives were starting to replace fists. After a firm talking-to, Nicholas sent the group of offenders, mostly teenage boys, on their way, except Roy and his younger brother, Roger, who had been doing their best to hide their faces in the crowd. Nicholas spotted them immediately, took them to the station, and locked them up for the evening.

His brief stint in the pokey did little to dissuade Roy, who continued to run with a group of older teens. He was arrested for burglary and, according to his military records, was “to be sent to Gatesville State School for Boys,” a notorious labor camp in Texas that implemented hard labor to reform juvenile offenders.

On his way out the door from El Campo Middle School to the sugar beet fields the spring of his fourteenth year, Roy informed his teacher he wouldn’t be returning in the fall. She tried to dissuade him, telling him he had potential and urging him not to throw his future away. But Roy never returned. After the harvest, when his siblings went back to school, he led the life of a school dropout, working odd jobs and giving more than half of his pay to his uncle and aunt. He still slept most nights in the attic with his brothers and ate at the family table.

One night his uncle caught him banging his way up the stairs, drunk after a night of too much beer. While Roy threw up, Nicholas launched into a lecture, pounding home the moral for what seemed like the thousandth time.

“Bad habits and bad company will ruin you, Roy,” Uncle Nicholas said. “Dime con quien andas, y te dije quien eres.” (“Tell me with whom you walk and I will tell you who you are.”)

2

“LOOK SHARP, BE SHARP, GO ARMY!”

AROUND THE TIME Roy dropped out of school, Nicholas attempted to channel Roy’s anger and quick-to-fists temperament into something positive—boxing—and for a time Roy excelled, making it to the state championship at the Will Rogers Coliseum in Fort Worth. There he was soundly beaten in his first match. The boy who won, living up to the code of sportsmanship taught by Golden Gloves, offered Roy a handshake in the locker room afterward, telling him, “You gave me a good fight.” In response, Roy wrestled the kid into a bathroom stall and shoved his head in a toilet.

When he turned around, Roy saw a look of surprise and disappointment in the eyes of the other fighters, the coaches, and Roger, all of whom had witnessed his rage. Their stares tore into his conscience. Though this was the end of Roy’s Golden Gloves days, it also represented a turning point in his life. For the first time, Roy felt regret instead of satisfaction from a fight he had initiated. He was ashamed of himself. He apologized to the boy, his coach, his uncle, his grandfather, his aunt, and his siblings, many of whom were still fighting in Golden Gloves. He even confessed his sin at church.

Whatever it was that had clicked, Roy finally understood what it meant to dishonor the Benavidez name, and he wanted to fix it. He wasn’t sure how, but he was going to someday make it right. The way he saw it, he had two options for now: go back to school and get an education or continue working and contributing to the family’s living expenses.

Embarrassed by his academic struggles, Roy later admitted that pride was what kept him from going back to school. He got a job pumping gas at a service station that was walking distance from the Benavidez house. He frequented the local Firestone tire shop, picking up parts for the gas station and skimming through car magazines, dreaming of building his own hot rod someday, once he could afford to move out of the attic.

Eventually, Art Haddock, who ran the counter and did the bookkeeping for Firestone, offered Roy a job making deliveries, changing tires, and cleaning up. Mr. Haddock, as Roy called him, was also a preacher at a Methodist church and a part-time mortician and funeral director. He understood better than most how precious life is, and he took a personal interest in seeing that Roy didn’t throw his away.

Mr. Haddock always kept a Bible close by and referred to it often, as though it was the shop’s employee handbook. If Roy cursed while trying to loosen a lug nut on a tire, Mr. Haddock would call him over and find a pertinent verse about taking the Lord’s name in vain. If Roy left a job unfinished, Mr. Haddock would thumb through and find an apostle with an appropriate lesson. From Genesis to Matthew to Paul, he delivered the Gospel, preaching to Roy as he preached to his own children.

Over the course of two years of changing flats and selling tires, Roy opened up to Mr. Haddock, sharing with him much of his past—the heartaches, the hardships, the racism, the fighting, the regrets, and the shame he’d brought to the Benavidez name. Roy presented them as obstacles that had held him back, but Mr. Haddock explained that each obstacle had taken him down a unique path, that there was a reason for each and every one of them. “God makes no mistakes,” he told Roy.

One day, a representative from the Texas National Guard came into the shop and asked if they would hang a recruiting flier in the window, a flier with a photograph of one of Roy’s childhood heroes, Captain Audie Murphy. After the Korean War began in June 1950, Murphy—in spite of his fame as the most decorated soldier in World War II, his bestselling autobiography, To Hell and Back, and his celebrity as a movie star—had shown his support for the war by joining the National Guard, both to serve in the field and to have his photograph used on recruitment posters. His unit, the 36th Infantry Division, was not called into combat during the war, but Murphy was a skilled and effective leader who trained and drilled new recruits.

Roy, s

eventeen at the time, spoke to a recruiter, then to Nicholas and Mr. Haddock. They all, especially the recruiter, thought the Guard seemed like a good idea—a chance to test the waters of the military. Roy signed up.

Aside from his family, the Texas National Guard was the first real team that Roy had ever been part of. He wore the uniform with pride, spending a fair amount of time in front of the mirror admiring how he looked. From his first days in the Guard’s basic training, when many complained about the hard work, he considered the military life fun and interesting. “Better than changing tires,” he told Mr. Haddock when he returned from basic training. To Roy, the physical side of it was nowhere near as exhausting or monotonous as working in the fields. Overall, it was a pretty good deal. Three meals a day, a roof over his head, hot showers, his own bed, and some extra money in his pocket each month.

After two years of part-time service (two weeks each summer, plus one weekend a month) in the Guard, juggled with his job at the Firestone shop, Roy had risen to the rank of corporal. He could envision sergeant stripes on the horizon—but not in the Guard. “Look Sharp, Be Sharp, Go Army!” was the Army’s recruiting slogan at the time, and that was Roy’s plan: to join the real Army. He was going to become a paratrooper, see the world, and make his family proud. He would bring honor to the Benavidez name.

—

ON MAY 17, 1955, Roy took his Guard papers to the main recruiting depot on Austin Street in Houston, Texas. He strutted his 130 pounds of machismo past the Marine and Air Force recruiters and stood before a sergeant sitting at the U.S. Army desk.

“Sir,” he said, “I want to go Airborne.”

What happened next became legend among Roy’s pals at his hangout in later years, the Drop Zone, a café and bar next door to the San Antonio Special Forces Association clubhouse near Fort Sam Houston. According to one retired paratrooper, “The sergeant looked over at Roy and said, ‘I don’t think you’re big enough for the Airborne.’ ” Accounts of what happened next vary, but the gist remains the same. “Roy got right up in the sergeant’s face and said, ‘I can cut you down to my size quick enough.’ ”

Roy hadn’t even a split second to regret his hot temper before the Marine recruiter appeared at his side. “Son, I think the Marines could use a young man like you,” he said. But an Army captain quickly stepped in and sat Roy down in front of the now chuckling sergeant. “Get lost,” he said to the Marine. Then, shaking Roy’s hand, the captain said, “You’re Army all the way, son. We need tough guys like you.”

Roy explained to the grinning sergeant that he’d served three years in the Texas National Guard, that he had already made the rank of corporal, and that he’d been told by another recruiter that he could go directly to advanced individual training (AIT)—a fast track to a chance at Airborne. The sergeant nodded the whole time, right up to the moment Roy signed on the dotted line and committed to three years in the United States Army, solemnly swearing “to defend the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic…. So help me God.” A few days later Roy discovered that the recruiting sergeant had ignored his papers from his years in the Guard and that he would instead be a raw recruit, starting from the ground up.

And so, nineteen-year-old Private Benavidez headed back to basic training—with gifts from both of the father figures in his life. Mr. Haddock put his hand on Roy’s shoulder and said, “The Lord bless thee and keep thee: The Lord make His face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee: The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee, and give thee peace.” Mr. Haddock then gave Roy something in parting no man had ever given him before. “He put his arms around me and gave me a hug. My first abrazo, from one man to another, came from an Anglo.” Nicholas sent him off with five words, and his voice cracked a little when he said them: “I’m very proud of you.” Roy turned quickly to hide his own emotions and tearing eyes. It wasn’t the words alone that brought the tears; it was looking into his uncle’s eyes and knowing how deeply the words were felt.

—

AFTER EIGHT weeks of basic training at Fort Ord, California, Roy traveled to Fort Carson, Colorado, for another eight weeks of AIT.

The last time he’d been in Colorado was on his hands and knees thinning sugar beets with a short-handled hoe. Now, just four years later, Roy stood tall and proud, rifle in hand, a squad leader, chosen by a platoon sergeant who built him up after realizing that Roy would not be beaten down. He instilled confidence in Roy, both in the field and in the classroom. “I ate it up,” Roy said. “I discovered what a kick it was to sit in the front of the class and have the first answer rather than to hide in back and hope the teacher didn’t call on me.”

He left AIT with orders for overseas duty; he was going to Korea. The war was over, but he would help secure the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. He returned to Texas for a two-week leave before embarking, stopping first in Cuero for a short visit with his half sister, Lupe. During that brief stay he came to the conclusion that despite being born in Cuero, El Campo was home, and that’s where he headed next.

He was thrilled when Salvador invited him to sit down with the younger cousins and nephews, who now gathered around him to listen to his stories as a soldier. There were no tales of battle yet, except for one incident when Roy and a buddy ran into a pair of skunks while crossing a field during night training maneuvers. That battle, Roy said, shaking his head, was clearly won by the skunks. His sergeant ordered them to burn their uniforms. The children held their noses and giggled when he told them how, because of the smell, he was forced to march naked far behind the others.

Roy didn’t mention to anybody, especially to Nicholas, that he had yet to control his fists, that he had gotten into a couple of scraps, even though they were now few and weeks between. And when he stood before his higher-ups—most of whom were combat veterans from Korea or World War II, the old-school, “brown shoe” Army—he got the feeling, from the light punishment they always administered, that they felt whoever he’d socked had it coming.

Roy’s aunt Alexandria had told him that his blood was both Mexican, from his father, and Yaqui Indian, from his mother; Roy had studied the tribe and was intensely proud of his lineage. Because the Yaqui were fierce warriors, he felt that his “quick fists” temperament came from those genes. He described the tribe as “the toughest, meanest, and most ornery group of Indians that ever lived. Back when Cortés was conquering most of Mexico, he wisely chose to avoid the northern deserts, where the ‘wild men’ had…killed and eaten whole armies of Aztec and Toltec who had been trying to conquer them for hundreds of years.”

—

IN 1956, Private First Class Benavidez was promoted to Corporal Benavidez and reported for duty at a base in Berlin, West Germany. He was a good soldier; not a model soldier, but a good one. He still tended to act and then think—“Ready, fire!”—without taking the time to aim. That impulsiveness was his glitch in life. It had gotten him sent to the principal, in hot water with Nicholas, in trouble with the law. And he might have been wearing those Airborne wings on his chest by now had he not been busted down in rank a few times. But he was learning.

In 1957 Berlin, the Wall between East and West still stood, and American soldiers stationed there were told their actions represented the United States of America and to keep that in mind when they were off base. A few weeks shy of the end of his sixteen-month duty assignment in West Germany, Roy and some friends went out for a Saturday night on the town. Outside a club, Roy overheard a heated argument in English between two men in civilian clothes; he recognized them as a couple of new second lieutenants from his unit. One was sloppy drunk and refusing to get into a cab. Roy walked up to the other young officer, introduced himself, and asked if he needed a hand.

“Sure,” the man said, but when Roy reached over to help get the more inebriated officer into the backseat of the cab, the latter pushed Roy away and told his buddy to get “this little Mexican no

ncom” off of him, punctuating his outburst with more racial slurs.

One of Roy’s friends said, “Deck him!” and Roy balled his fist, pulled back, and sent the lieutenant reeling into the backseat with a solid punch to the face. His buddy hopped in beside him, and the cab took off for the base.

Roy regretted instantly what he’d done. Back at base, he stressed over the potential repercussions all night. He had struck an officer, in public, with witnesses. That was a criminal offense.

He held his breath between prayers all the way till Monday, when he was summoned to the office of a captain to whom the second lieutenant Roy had knocked senseless reported. The captain, who wore a West Point class ring, was reading a file. Behind him was a plaque on the wall that read, “I do not lie, cheat or steal nor tolerate those that do,” the honor code of West Point. Beneath were three words: “Duty, Honor, Country,” the West Point motto.

“Corporal,” he finally said, “you know why you’re here. I understand there was a little trouble in town Saturday night. I’ve read your file, and you’ve been a pretty good soldier up until now. I’m going to ask you something. Think before you answer me. Corporal, did you or didn’t you strike an officer Saturday night?”

He leaned back, crossed his arms, and waited.

Roy’s superior, a sergeant, looked on while Roy tried to figure out whether this captain had just offered him a second chance. Maybe he knew the second lieutenant was a hothead drunk. Maybe he thought he’d deserved it. Or maybe he was going to base the extent of his punishment on Roy’s answer. It was his word against two lieutenants. He could lie.

“Yes, Sir,” Roy said. “I hit that officer.”

Legend

Legend The Last Season

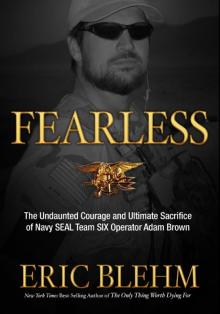

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For