- Home

- Eric Blehm

Legend Page 4

Legend Read online

Page 4

The sergeant looked at Roy in disbelief, and the captain didn’t say a word. After what seemed an eternity, he sent them into the hall, where Roy’s sergeant laid into him for being the stupidest corporal who’d ever walked the face of the earth. While his sergeant continued to berate him for looking a gift horse in the mouth, the door to the captain’s office swung open.

“Sergeant,” the captain said, “return the PFC to his duties.”

The sergeant’s jaw dropped, and Roy let out a sigh of relief. The captain had demoted him from corporal to private first class. He’d only lost a stripe.

Before Roy returned to the States, the captain called him back into his office to ask why he had risked so much by confessing. Roy told the captain that he had been inspired by the West Point plaque behind his desk, which bore the same message he’d been hearing his whole life, just worded differently. He told the captain he wanted a career in the military, and he didn’t want that career to be based on a lie.

Many things in Roy’s life suddenly made sense to him. All those lectures, the morals, the Bible verses, everything he’d been spoon-fed for years in both Spanish and English by Grandfather Salvador, Uncle Nicholas, Aunt Alexandria, and Mr. Haddock translated perfectly into Duty, Honor, Country—Deber, Honor, País. The realization was a gift for Roy, a regalo that the West Point plaque had wrapped up in three words and put a bow on.

He made a personal vow that day. Even though he was a noncommissioned officer, he was going to adopt West Point’s code—an officer’s code—as his own. From there on out, he would do his very best to take a deep breath before pulling the trigger.

—

ROY RETURNED to El Campo for a thirty-day leave with one goal: to ask for a woman’s hand in marriage. Her name was Hilaria “Lala” Coy, and he’d been writing to her throughout his deployment to Germany.

The great thing was that Lala, with her father’s blessing, had been writing him back; this was because Roy had followed the proper courting protocol, having first asked Lala’s father if he could correspond with his daughter. During his leave, Roy requested permission to call upon Lala, met her in the company of her family, and then his family, and then dated her with a chaperone. Ultimately, he was allowed to sit alone with her on her porch.

By the end of Roy’s leave, Lala knew every chapter of his journey to serve his country—from his early years on the streets of Cuero to the fields of Colorado and South Texas to the times they’d noticed each other during community events, church, and the weekends when families came together for picnics and baseball games in the park. She teased him about one game in particular.

It had been the early 1950s, when the men and boys played while the women and girls watched. During one inning, Roy was so busy smiling and staring at Lala in the bleachers from his position in the outfield that he didn’t see a pop fly when it plopped down in the grass beside him. His team yelled and screamed at him to pick up the ball, but nothing broke his trance.

They were engaged on December 30, 1958, just before Roy shipped out to military police (MP) school at Fort Benning, Georgia. Fort Benning was eight hundred miles away from El Campo, not a terribly long journey on a weekend pass when you’re in love and driving a 1955 Chevrolet hardtop.

Lala and Roy were married in a 6:30 a.m. mass at St. Robert Bellarmine Church in El Campo on June 7, 1959. He wore a tuxedo; she wore a long lace gown and carried an orange-blossom bouquet. With eighteen attendants and 150 guests, both families were well represented in the all-day event, which included a reception in the parish hall, a barbecue at noon, and a four-tiered wedding cake. They received traditional blessings from Lala’s parents at their home and from Nicholas and Alexandria at theirs. Their nuptials were complete when Lala and Roy made their secret promesas—promises for their lives as husband and wife—before a Catholic shrine.

—

THE NEWLYWEDS moved to Fort Gordon, Georgia, where Roy completed MP school and was selected to stay on after graduation and serve as the driver and personal guard for the post commander, General H. M. Hobson. At the same time, he put in two formal requests for jump school. Both were denied. He wondered if the times he’d been busted down in rank early in his career were the reason for the denials. The paratroopers were the elite in the Army, and the elite move up, not down.

“Patience and prayer,” Lala told him.

One afternoon General Hobson announced to his staff that the commander of the 101st Airborne Division, General William C. Westmoreland, would be visiting the base to address the officers. He assigned Roy to be Westmoreland’s driver.

While some generals were all business and treated their drivers like nothing more than drivers, Roy found Westmoreland to be friendly and approachable. The general even asked him a few polite questions, such as where he was from—and then the one question Roy had been praying for.

“Sergeant, have you ever thought about going Airborne?”

Being the chauffeur for a general is a cushy job in the Army, one that an unmotivated soldier could happily ride all the way to retirement. Roy later wondered if the general made a game out of asking that question of all his drivers, for entertainment value.

Roy could barely contain himself; he’d been trying to figure out a way to broach the topic before the general left the base. “Yes, Sir,” he said. “Ever since I was a kid, even before I joined the Army. I’ve applied but haven’t gotten accepted. I just want a chance, Sir.”

“You must want to go pretty bad,” the general replied.

“Yes, Sir. I’m up for reenlistment in a few weeks; I’ll give it another try.”

Twenty-four hours later, Roy drove Westmoreland to a waiting plane at Bush Field, Fort Gordon’s airstrip, opened his door, and saluted as the general walked toward the aircraft.

“Good luck, Sergeant,” Westmoreland said, then looked down and walked away in silence.

When Roy’s reenlistment papers showed up two months later, they included an authorized invitation to attend jump school, compliments of Westmoreland himself.

—

JUST LIKE all the times he jumped from the loft of the cotton warehouse in Cuero, Roy never hesitated when he leaped from a low deck, then a higher deck, then a tower, and ultimately out of an airplane. Floating through the sky beneath the silk of a parachute washed him of his past. He was Airborne now, the paratrooper who had once lived only in his dreams. There was no horizon; he could see forever.

Roy returned to Fort Gordon at the end of 1959 with jump wings on his chest and a skip in his step. He and Lala packed their belongings, said good-bye to Georgia, and headed to North Carolina, where he was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg.

As they traveled—sometimes while stopped at a café eating a burger and a shake, sometimes when they were cruising on the open road—they’d talk about their future and the family they prayed to become. The question was not whether they would have children, but how many they’d be blessed with.

“Getting an education is the most important thing in your life,” he planned to tell them, just as Salvador had told him. Their studies would be their job, their contribution to the family, their way of honoring the Benavidez name. Their school year would not be interrupted by the harvest. They would graduate from high school, and then they would go to college. They would have degrees to hang on their walls. This was the dream he and Lala shared as a young couple looking toward tomorrow. Their success would be the measure of his success. The key to it all, Roy knew, was the plan he had mapped out in the Army.

In early 1965, they bought their first home, a mobile one. A lot of young Army couples were doing the same. With a trailer, no matter what base they ended up on, they could open the door and they were home. They celebrated their sixth wedding anniversary parked at the Bonnie Doone Trailer Park, not far from the main gates of Fort Bragg. There was an Airborne patch inside the window next to the door, a

potted plant on each side of the front step, and on a wall a framed certificate, the equivalent of a high school diploma, which Roy had earned while taking the necessary courses, in addition to the heavy load of career courses for his military occupational specialty (MOS) as an Airborne infantryman.

Fall was in the air when Roy checked the air and tread on the trailer’s tires, prepping it for the road. For the fifth time since they had married, they were moving. By the end of October the trailer was parked in the empty lot next to Lala’s parents’ home back in El Campo, and Roy was gone—but not off training or attending some short-term school. Lala’s husband, Sergeant Roy Benavidez, the father of the baby growing inside her, had gone to war.

—

THE OFFICIAL date of the beginning of America’s involvement in the Vietnam conflict would be argued for decades to come, including whether or not the weapons and training the OSS provided to Ho Chi Minh’s Vietminh guerrillas during July and August of 1945 qualified as “involvement.” Furthermore, did that brief period when the United States and the Vietminh were allied against the Japanese give Ho Chi Minh the credibility that would catapult his movement into the unified “One Struggle” of the Vietnamese people for independence? Under Ho’s (or as his people referred to him, Uncle Ho) communist leadership, the Vietminh battled the French in the First Indochina War for almost nine years, until May 7, 1954, when the battle at Dien Bien Phu forced the French into a peace conference the following day.

The conference in Geneva, Switzerland, sought to bring a lasting peace to Indochina. Its attendees hashed out a cease-fire, a promised future election, and a plethora of other diplomatic solutions, only a few of which would stick for more than a couple of years. The first was the decision that Vietnam would be split at the 17th parallel, with President Ho Chi Minh temporarily leading the communist north and a French-colonial-minded president, Ngo Dinh Diem, temporarily leading the capitalist south. The election that would reunify the country was set to take place in two years. But Diem, anticipating that the popular Ho would prevail in the slated national election, postponed it, and then canceled it completely.

Vietnam remained split, with Diem ruling the south autocratically (to the chagrin of the U.S government that had backed him for eight years) until he was assassinated on November 2, 1963, during a military coup led by a senior general of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), Duong Van Minh. The coup was encouraged, if not orchestrated by agents of the Central Intelligence Agency (the successor to the OSS), under the administration of President John F. Kennedy.

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy himself was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, and the anticommunism torch was passed to his vice president, Lyndon Baines Johnson. LBJ solemnly addressed Congress five days later, mourning the loss of “the greatest leader of our time.” “And now the ideas and the ideals which he so nobly represented must and will be translated into effective action. Under John Kennedy’s leadership, this nation has demonstrated that it has the courage to seek peace, and it has the fortitude to risk war. We have proved that we are a good and reliable friend to those who seek peace and freedom. We have shown that we can also be a formidable foe to those who reject the path of peace and those who seek to impose upon us or our allies the yoke of tyranny. This nation will keep its commitments from South Vietnam to West Berlin.”

The U.S. commitment to General Duong Van Minh as president of South Vietnam lasted only a couple of months. He was overthrown by another general in the second of a string of seven military coups in less than a year and a half. During this period, a communist movement—the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, or Vietcong (VC), and what everybody suspected was really the puppet of Ho Chi Minh and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA)—made great strides in what had been a growing insurgency. Number one on the Vietcong’s charter had been to “overthrow the camouflaged colonial regime of the American imperialists and the dictatorial power of Ngo Dinh Diem, servant of the Americans, and institute a government of national democratic union.” By the time a lasting leader, General Nguyen Van Thieu, became president of South Vietnam in June of 1965, the Vietcong were firmly entrenched, with guerrillas sneaking over the demarcation line of the 17th parallel to recruit locals and conduct acts of terrorism against the people of South Vietnam, kill American advisers, and engage the South Vietnamese Army in the small-scale but effective attacks of warfare.

The attacks were widely publicized, creating reams of evidence that justified the deployment of more and more American military advisers to aid the South Vietnamese Army in its fight against the communists; what had been hundreds of advisers soon became a few thousand.

The United States had fought communism overtly on the Korean Peninsula and covertly in its bastions worldwide. Now Uncle Sam was keeping a wary eye on Uncle Ho, anticipating an all-out invasion across the line of demarcation. Three U.S. presidents—Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy—had vowed to repel communist aggression in Indochina; the U.S. government, led by the fourth U.S. president to fervently oppose communism, Lyndon Johnson, sought and received congressional approval to increase American troops by the tens of thousands, to stop it at the 17th parallel.

Both the United States and North Vietnam accused the other of committing acts of terrorism and crimes against humanity. The reasoning and the politics, the truths and the lies, and the justifications and the history that would be written would be hotly debated forevermore.

—

ONE THING about Vietnam was certain, at least for Lala Benavidez: the quiet fear and sense of pride she felt when Roy was called to fight, called to do his duty, called to go to “A New Kind of War,” as Time magazine described it on October 22, 1964. It was the same month Roy learned he would deploy as a military adviser to the South Vietnamese 25th Infantry “Tigers.” He was going to fight the red tide of communism before it crossed the oceans and crashed onto the shores of America. He’d be battling “the lethal little men in black pajamas” who, just three months earlier, had “roamed the length and breadth of South Viet Nam marauding, maiming, and killing with impunity,” as Time reported. “No highway was safe by night, and few by day; the trains had long since stopped running. From their tunneled redoubts, the communist Vietcong held 65% of South Viet Nam’s land and 55% of its people in thrall.”

The Vietcong—aka VC, Victor Charlie, or just Charlie—were the new bad guys on the block, the insurgent instruments of the communist plague vying to take over Indochina, one country at a time. If South Vietnam fell, U.S. officials felt, so, too, would the rest of Southeast Asia, like dominoes, gaining momentum as they toppled one after the other all the way to the American heartland. So went the political justification for U.S. involvement. The Vietcong, in Roy’s mind, were no different from the Nazis and the Japanese in World War II.

By October 1, 1964, America had committed 125,000 troops to advise and fight beside the South Vietnamese Army. Sergeant Benavidez was part of what Time called “one of the swiftest, biggest military buildups in the history of warfare…. Day and night, screaming jets and prowling helicopters seek out the enemy from their swampy strongholds in southernmost Camau all the way north to the mountain gates of China.”

Three short weeks after the American surge in troops, Time reported, “The Vietcong’s once-cocky hunters have become the cowering hunted as the cutting edge of U.S. firepower slashes into the thickets of communist strength. If the U.S. has not yet guaranteed certain victory in South Vietnam, it has nonetheless undeniably averted certain defeat. As one top-ranking U.S. officer put it: ‘We’ve stemmed the tide.’ ”

In 1965, the majority of Americans stood behind those serving in Vietnam. They were answering the call of duty and honoring the ideals of their late commander in chief, JFK. The president had made a promise to the world in his inaugural address four years earlier that Americans would “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to ass

ure the survival and the success of liberty.”

President Johnson echoed JFK’s sentiment in a press conference in July 1965. “We did not choose to be the guardians at the gate, but there is no one else. Nor would surrender in Viet-Nam bring peace, because we learned from Hitler at Munich that success only feeds the appetite of aggression. The battle would be renewed in one country and then another country, bringing with it perhaps even larger and crueler conflict, as we have learned from the lessons of history…. As long as there are men who hate and destroy, we must have the courage to resist or we will see it all, all that we have built, all that we hope to build, all of our dreams for freedom—all, all will be swept away with the flood of conquest.

“So, too, this shall not happen. We will stand in Viet-Nam!”

—

ROY DIDN’T ship to Vietnam with the Marines, nor did he parachute in as a paratrooper; he flew into the war on a chartered commercial airliner. Once there, he taught the South Vietnamese how to counter the insurgency, while he simultaneously was learning how to survive the nuances of a jungle war. Most of what he’d learned in training was based upon conventional war, where the front was generally in front of you and the rear was behind. But the Vietcong—Charlie—didn’t fight that way; it wasn’t the “able, baker, Charlie, dog, easy” war Audie Murphy had fought in the 1940s. Everything, right down to the U.S. military’s phonetic alphabet, had changed. This was the “alpha, bravo, Charlie, delta, echo” war. Charlie. Wouldn’t you know it? “Charlie” for both wars. Charlie was everywhere…

Roy had been trained to keep a wary eye on the locals, who appeared as innocent, smiling villagers by day, but were potentially AK-47-wielding, rocket-toting Vietcong guerrillas by night. Still, he couldn’t help respecting the Vietnamese people when he’d see families working long hours side by side in the fields, the young children barefoot and half naked, tending their crops.

Legend

Legend The Last Season

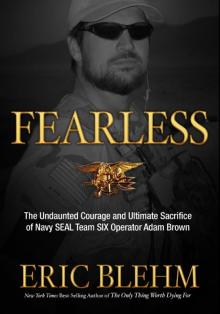

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For