- Home

- Eric Blehm

Legend Page 6

Legend Read online

Page 6

He became the nightly entertainment for the men recuperating around him, who cheered him on every time he fell. It took a week of trying before he was able to raise himself all the way up between the nightstands by pressing his back against the wall and using his arms. This brought his legs almost underneath him, but mostly he was supported by his triceps and shoulders. “I was just sort of hanging there,” Roy said. “I tried to put weight on my legs, and a burning pain shot through my back that felt like I’d been stabbed with a red-hot knife. I collapsed against the wall, and slid to the floor.”

The nurses came running when they heard the cheers. Once they understood that he was trying to walk, they sent him to therapy.

After a week of painful therapy and his own nightly regimen, Roy stood—tears streaming down his cheeks, panting like a dog, hands hovering six inches above the nightstands. He was bearing his own weight.

Soon after, sensation returned to Roy’s toes. He was able to wiggle them. He shuffled a few inches, more and more each day, until he was pushing his own empty wheelchair down the long hallway to the chapel, where he stopped asking questions of God and instead gave thanks for what he realized was a miracle.

The doctors—in particular the chief surgeon, who had originally given Roy the news that he’d most likely never walk again—congratulated him. After five months in the hospital, he had far exceeded their expectations. Then they tried to give him a medical discharge from the Army. He pleaded with them to reconsider. While many young men were doing all they could to avoid military service, Roy didn’t want this get-out-of-jail-free card; he wanted to return to the 82nd and get on with his career.

—

EARLY IN the summer of 1966, Roy put on a crisply starched uniform and walked out of the Beach Pavilion at Brooke Army Medical Center on shaky legs, holding the hand of his wife. Lala, well into her final trimester of pregnancy, had proven herself a warrior of her vows, standing proudly by her man: “for better or for worse, in sickness and in health.” They packed up the trailer and returned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, arriving in time to watch the fireworks on the Fourth of July. On July 31, their first child, Denise, was born.

While Lala settled into motherhood at the Bonnie Doone Trailer Park, Roy began his new job as the administrative assistant to the personnel sergeant with the 82nd Airborne Division. His daily mission was to help navigate Airborne soldiers and their wives through the minefields, barbed wire, and coils of red tape that lay between them and the benefits associated with their “membership” in the U.S. Army.

Roy was good at what he did, and thankful that the Army had kept him in service, but in his heart he knew he was a soldier meant for the field. He dutifully stamped forms, typed reports, cleared the in-box, and filled the out-box, but his mind was back in Vietnam. Despite the terrible things he had seen, despite being nearly killed and paralyzed, he longed for that intense feeling of being fully alive he’d experienced in a combat zone. Now that he was a parent, he realized that the protective emotion he’d felt for his men was nothing less than paternal. Like a sidelined football player watching his team take the field, he watched the soldiers at Bragg train and deploy.

Always have an option. In a village, on a road, along a jungle pathway—and there in his office at Fort Bragg—Roy was always keeping his eyes and ears open for options. Though he was grateful to be alive, the desk, he knew, would kill him—not quickly like a booby trap or an ambush, but worse. It would kill him slowly.

4

GREEN BERET

THE STUFF OF Roy’s childhood dreams, the Airborne paratroopers, had been the Army’s most elite infantry troops in World War II. But in Vietnam, the airmobile tactic of inserting hundreds of soldiers by helicopter into precise landing zones in the jungle made parachute assaults passé. Special Forces—the Green Berets—although still airborne jump-qualified, took the front seat both on the battlefield and in popular culture as the new “most elite” ground troop, whose strength came, in great part, from unconventional tactics and individual versatility rather than from overwhelming numbers and conventional maneuvers and firepower. They were the “Swiss Army knife” of soldiers, who could be called upon for any kind of mission but who specialized in guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency—tailor-made for fighting the communists in Vietnam.

The U.S. Army was serious about morale and esprit de corps, and the foundation for any soldier’s pride came from his unit’s identity and lineage. Special Forces tactics were rich in history and could be traced back to the American Revolution and the Civil War. The Green Berets’ mission and organization, however, had evolved from World War II military units, including the 1st Special Service Force—aka the Devil’s Brigade—Merrill’s Marauders, and Darby’s Rangers, and in particular the Jedburgh teams of the Office of Strategic Services.

That the OSS had trained and provided weapons to Ho Chi Minh twenty-two years earlier was still highly classified information.

Before his first tour, Roy had signed up for an opportunity to qualify for the Green Berets and been accepted. Now he wondered what it would take to get another shot. The John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School was right there at Fort Bragg, so Roy helped himself to a stack of the inches-thick training manuals that constituted the curriculum of the Special Forces Qualification Course (Q Course). On the inside was a quote pulled from the address JFK presented to the 1962 graduating class at West Point: “This is another type of war, new in its intensity, ancient in its origins—war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins; war by ambush instead of by combat; by infiltration instead of aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him. It requires—in those situations where we must encounter it—a whole new kind of strategy, a wholly different kind of force, and therefore, a new and wholly different kind of military training.”

The Green Berets gave Roy hope, and he dreamed of joining their ranks—something he didn’t dare mention to Lala. He secretly began to plan. His aspirations might have been fogged by the one thousand to fifteen hundred milligrams of Darvon he was taking daily for the stabbing pain that shot up his legs and into his back, but as a friend of Roy’s says, “This was a guy who doctors said would never walk again. ‘I can’t’ wasn’t in his vocabulary.”

Roy’s personnel file already showed that he met all four of the requirements for Special Forces qualification: he’d volunteered for the Army; he was airborne jump qualified; he had personally requested to try out for the Special Forces (and been accepted); and, being a sergeant, he held a noncommissioned rank. The problem was that his wounds and hospital stay meant he needed to “refresh” his jump status; in addition, the documentation saying he’d been accepted for the Q Course had been sent before his tour and had since expired—or so he thought, since it was no longer in his personnel file.

The other, seemingly insurmountable, issue was the level of his physical fitness. The Special Forces training and qualification process—like that of the Navy SEALs, Marine Corps Force Recon, and Army Rangers—was as grueling as it got, with very few making it through. In order to wear the coveted Green Beret you had to prove you were the type of soldier who would die rather than quit.

Roy couldn’t get the Green Berets out of his mind, reading everything he could about them, watching them train in the field; he even received permission to sit in on a few of the classes. In a military town like Fort Bragg in 1966, it was nearly impossible to turn on the radio and not hear “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” written and performed by Special Forces staff sergeant Barry Sadler in honor of Specialist 5 James P. Gabriel Jr., an early Special Forces adviser who was shot in the chest during a Vietcong attack on his four-man advisory team and a group of Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG; pronounced sid-gee) trainees near Danang four years earlier. Critically wounded, the twenty-four-year-old Green Beret continued to defend their position and had radioed for reinforcements until he was ov

errun and captured. The VC executed him.

Fighting soldiers from the sky

Fearless men who jump and die

Men who mean just what they say

The brave men of the Green Beret

—

THE GREEN Berets’ motto is “De Oppresso Liber”—“To Free the Oppressed”; those words made Roy reflect obsessively on the atrocities he’d seen in Vietnam. Staring at his daughter as she slept, watching her tiny chest rise and fall, often brought him to tears. He would think about the three children who were crucified by the VC. He would think about the wailing women and the man who had mourned their loss. They haunted him and fueled his desperation to get back into the fight.

Roy’s request to update his jump status was categorically denied because of his physical condition. Assigned to “light physical activity,” he was, according to the Army, destined for a desk. But the desk did provide for Roy, giving him an understanding of paper trails and how documents get lost in them—and if they can be lost, so, too, can they be found.

With a neatly forged, pocket-wrinkled authorization slip in hand, Roy smooth-talked his way aboard a crowded aircraft late in September 1966. He jumped three times that day. He went home, limping and in pain from a particularly jarring landing, with the news that they’d be getting fifty-five dollars extra that month in “jump pay.” Lala rarely raised her voice but would call Roy by their last name when she was really upset. “Benavidez,” she said sternly, “you know you’re not supposed to be jumping!”

What he didn’t share with her was that this was just the beginning of his plan. Now that he’d proven both to the Army and to himself that he could handle the air, he would conquer the ground. Every morning on base he walked, then jogged—gradually increasing the miles while decreasing what had become addictive pain medication. Less than a year after leaving the hospital, Roy had weaned himself completely off the painkillers and could run five miles without stopping. That was when the signed, stamped, and approved papers for Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez to transfer into the Q Course from two years before suddenly appeared in the stack of current requests.

“I broke a few rules back then,” Roy later admitted, “and it wasn’t the right thing to do. It was wrong. But my time was running out. I was over thirty and still pretty badly damaged. I wanted back into that war. [It] was the most horrible experience of my life, but I was a soldier…. I felt my life had been spared for a reason, and I knew that I couldn’t find it sitting behind a desk.”

—

LALA WAS happy to see the fire return to Roy’s eyes during those months of personal training, but in February of 1967, when he told her he had been given the opportunity to qualify for the Green Berets, she just shook her head and said, “Benavidez.” The thirty-one-year-old airborne- and infantry-qualified sergeant first class was older than most of the instructors at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, where he was assigned. His most recent duty had been as an administrative desk jockey with the 82nd Airborne Division, and before that he’d spent almost half a year at Brooke Army Medical Center convalescing from his wounds. On paper, he was not exactly prime Green Beret material.

But if his instructors were privy to Roy’s medical history, they never mentioned it. And, likewise, in a community of elite warriors where reputation is everything, Roy never spoke a word of his past wounds for fear he’d be marked as a liability among the men or, worse, that the instructors would beat him down harder than the others to be sure he had what it took.

He strove to be the gray man who blended in and never stood out. Unable to lead during physical training, he gave it his all to avoid being in the rear, consistently hanging somewhere in the central part of the tail of the group. Camouflaged naturally by his short stature and hunched over from sheer agony, he powered through requirements that included daily calisthenics—push-ups, sit-ups, leg lifts, squats, pull-ups, chin-ups, dead hangs—and double-time marching, forced marching, jogging, and running, eventually with a seventy-pound rucksack on his back. The crux of the physical tests was parachuting with minimal gear and five days’ worth of food and water into the woods, where, teamed up with a buddy, they were expected to both survive and stay oriented for twelve days, during which various objectives had to be accomplished.

Still, the physical training was for Roy the easy part. It was the MOI, method of instruction, and MOS, military occupational specialty, training and cross-training—the classroom training in particular—that weeded out the men unable to show their depth as a soldier, leader, technician, and instructor. If you couldn’t both master a skill and teach somebody else that skill—such as reassembling a broken-down M60 machine gun and naming off the function of each part along the way—you had no place on a Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha, an A-team. You had no right to wear the Green Beret.

An A-team is the basic operational unit of Special Forces, consisting of two officers (at the time a captain and a lieutenant), two operations/intelligence experts, two communications experts, two weapons experts, two medics, and two engineers (demolition experts). This twelve-man team is capable of building, healing, and destroying. In the event that any of the team is wounded or killed, all its members cross-trained to perform proficiently the basic duties of their teammates. In certain situations the unit can be split in half to operate as two six-man teams.

In Vietnam, the Special Forces mission focus was similar to Roy’s duties as an adviser during his first tour: he would be training and leading the South Vietnamese and indigenous tribes to fight the communist insurgency. But as a member of an A-team, he would likely be assigned to a remote Special Forces “A-camp,” where twelve Green Berets oversaw (or built) units of South Vietnam ARVN or CIDG soldiers, who, depending on the region, could be ethnic Chinese Nungs or Montagnard tribesmen. These A-team–led camps could be platoon strength, company strength, or in some cases multiple companies and were strategically located near high-traffic infiltration routes from Laos or Cambodia, as well as key provincial villages likely to be targeted by the Vietcong.

The A-team outposts were the eyes and ears of the countryside, the boonies—known as “Indian country” along the border. By patrolling, reconnoitering, and assessing the locals’ knowledge, they gathered information about enemy movements and strengths and reported it to intelligence headquarters in Saigon. At the same time, the camps provided protection for the local populations (from which the Green Berets would recruit, train, and ultimately build strong localized counterinsurgency forces that could handle their own anticommunist, pronational defense). This was the Special Forces mission. It was extremely dangerous work.

—

AFTER REVIEWING the results of a series of tests, the Special Forces training cadre would decide where best a trainee would contribute to a team. Roy qualified for both operations/intelligence and light and heavy weapons. In the field he could always manage, but he found himself overwhelmed in the classroom, especially because, as the ranking noncommissioned officer (NCO), he was expected to lead the lower-ranked NCOs while maintaining his own studies.

The training schedule was flexible, so sometimes new students cycled in to check off the boxes of their requirements. Roy found himself sinking, inundated by the workload, when a familiar face appeared, a soft-spoken fellow soldier from the 82nd named Leroy Wright.

Thank God, Roy thought when he realized that Wright, who was four years older, also outranked him. Roy handed the extra leadership duties over to Wright, who was happy to help, and the two became quick friends, having traveled similar career paths in the infantry, including tours in Korea’s demilitarized zone. But while Roy had served the standard one-year billet, Wright had volunteered for a second.

The winters in Korea were harsh, the American camps spartan, and the conditions in the postwar poverty-stricken land had made it one of the more undesirable overseas duties to pull. Why would anyone volunteer

for a second tour? Wright earned Roy’s abiding respect when he explained that he had fallen in love with a Korean woman who lived in squalor in an off-base shantytown. He had gone through a great deal of red tape and a second deployment in order to marry her and bring her back to the United States as a citizen.

When he and Roy reunited at the Q Course, Wright was a family man with two young boys; he had also served a tour in Vietnam, where he had been wounded by a grenade blast. Like Roy, Wright felt that he wasn’t done. The two men shared a strong sense of duty as well as an innate drive to better themselves and honor their family names, a purpose that was met by the Army. And they both quietly hoped for a second tour in spite of their families’ desire for them to remain stateside. Somewhere down the line, they promised each other as they shared photos of their kids, they would get their families together for a barbecue.

—

IT WAS common at the Special Warfare School for active-duty Special Forces soldiers, and sometimes foreigners, to join a class as a refresher or to add a skill set to their MOS. Such was the case when an instructor introduced Sergeant First Class Stefan “Pappy” Mazak to Roy’s class. It was an honor to have this combat veteran among their ranks, the instructor told his students.

Mazak was a five-foot-two-inch, forty-one-year-old Czechoslovakian “Lodge Bill” soldier who had fought with the French Resistance as a teenager, then with the French Foreign Legion. He was recruited in 1952 by the newly founded 10th Special Forces Group, under the Lodge-Philbin Act of June 30, 1950, which authorized the recruitment of foreign nationals into the U.S. military. The group’s mission had been to conduct guerrilla warfare against the communists in the event of a Soviet invasion of Europe.

While the invasion never came, Mazak gained fame and respect in other actions, including an emergency rescue mission to the Belgian Congo in the summer of 1960. Mazak was part of a four-man contingent tasked with rescuing and evacuating European and American citizens who were being systematically hunted down and killed by a violent rebel group. At one point, Mazak’s superior, First Lieutenant Sully H. De Fontaine, requested a Belgian platoon of paratroopers for backup when he was surrounded by “a band of about fifty threatening, gun-toting rebels,” according to Roy’s recount of the story. “The self-styled leader informed De Fontaine that ‘all whites were to die.’ Fontaine produced a grenade, pulled the pin, and said to the leader, ‘Okay, boss, shoot me. We will die together.’

Legend

Legend The Last Season

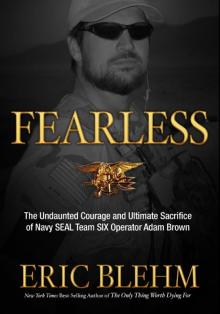

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For