- Home

- Eric Blehm

Legend Page 7

Legend Read online

Page 7

“For two hours the stare-down continued, with De Fontaine acutely aware that he could not hold the grenade firing lever forever…. Suddenly, Mazak emerged from the bush holding two submachine guns [and] fired wildly into the air as he screamed profanities at the top of his lungs. De Fontaine saw the fear in the eyes of his chief opponent and tossed the grenade into the midst of his captors. The remaining live rebels ran screaming into the bush, abandoning not only the refugees in the village but their arms as well. Later, Mazak apologized to De Fontaine for his outburst of theatrics, but stated, ‘I just couldn’t think of anything else to do at that moment.’ ”

When Roy’s instructor finished telling the story, the entire class rose to stand at attention while Mazak remained humbly seated. With some coaxing by the instructor, Mazak also rose, apologizing for his broken English. Roy paraphrased:

“We in this room are all men who believe that actions speak louder than words. If I can impart anything from my life as a soldier, it is this: There are only two types of warrior in this world. Those who serve tyrants and those who serve free men. I have chosen to serve free men, and if we as warriors serve free men, we must love freedom more than we love our own lives. It is a simple philosophy but one that has served me well in life.”

Roy was entranced, and he approached Mazak after class to ask if he would consider pairing up as study partners. Together they struggled through and completed the operations and intelligence course, and Mazak prepared to ship off to Vietnam.

Shortly thereafter, Roy was assigned to an A-team of fellow students, who “fought” in an elaborate mock unconventional war set in the rural counties of North Carolina. This was the Q Course final exam, during which teams faced real-world scenarios to test the depth of their training and adaptability under stress and against an opposing force.

Roy and his team made the cut, and he stood at attention as Colonel George D. Callaway presented him the certificate Roy would frame and display inside the Benavidez trailer. “Be it known,” stated the certificate, “Staff Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez has successfully completed the U.S. Army Special Forces Training Group (Airborne) Course of Instruction. He has demonstrated proficiency in Special Forces Tactics and Techniques, and has specialized in M.O.S. 11B/11C. Given at Fort Bragg, North Carolina this 29th day of September, 1967.”

Then Roy received what he would cherish for the rest of his life; what President Kennedy had called “a symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction in the fight for freedom.” His green beret.

5

THE SECRET WAR

BASED OUT OF Fort Bragg, Company E of the 7th Special Forces Group became Roy’s new home. There he continued honing his skills as an operations and intelligence sergeant, destined for a foreign assignment either to a South American country, because of his fluency in Spanish, to teach counterinsurgency tactics, techniques, and procedures to allied government troops—or back to Vietnam.

The war he’d deployed to two years earlier had steadily escalated, with LBJ’s most recent surge in troops bringing American forces in Vietnam to more than 400,000. By late 1967, close to half a million Americans and 250,000 South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers were fighting an estimated 400,000 North Vietnamese Army and Vietcong soldiers in a country roughly the size of the state of New Mexico. It was a war of attrition, a bloodbath in which American and ARVN forces had killed roughly 180,000 NVA/VC, and the NVA/VC had killed 16,250 American and 24,600 ARVN soldiers. These numbers did not include civilian deaths on either side.

The Americans and South Vietnamese were confident the North Vietnamese could not sustain such losses indefinitely. The key to victory would continue to be a combination of devastating airpower—tactical bombers and massive B-52 strategic bombers that targeted industrial sites in the north and enemy positions in the south—and air mobility, the use of helicopters for troop movements, resupply, medical evacuation, and tactical air support for ground troops. Massive search-and-destroy operations had become the most effective ground strategy to locate and wipe out the enemy in their jungle redoubts.

Assault helicopter companies flew combat assaults, inserting hundreds of troops into an objective area. Accompanied by heavily armed helicopter gunships, these Hueys, or “slicks,” flew in formation to a landing zone (LZ), where they briefly touched down, one after the next, in a line or a staggered trail (depending on the LZ) and just one or two rotor-disc (blade length) distances apart. Six soldiers would spill out of each, yielding platoons or entire companies of men in jungle clearings, on roads, mountain ridges, or the berm-like dikes that surrounded rice paddies.

A wave of landings could systematically surround a village, section of jungle, valley, or other suspected enemy stronghold. Assaults could be small in scale—a couple of platoons pushing through a village. Or they could be much larger, perhaps employing a horseshoe-assault strategy with some troops positioned as blocking forces on the sides and others configured at the open end of the horseshoe, pushing forward. If Charlie was there, kill him, capture him, or drive him toward the blocking forces that would do the same. When the job was done, the Americans and their ARVN counterparts would search the bodies and gear for intelligence, blindfold any captured enemy, bind their hands and feet for security, call the helicopters back in, and fly back to their staging area or base camp, where prisoner interrogations would take place. Dead enemy bodies—not territory gained or held—were the measure of success.

Corpse by corpse, the Americans were winning the battles and destroying enemy weapons, food, medical, and ammunitions caches in the process. But with its population of over 16 million, the north was prepared to replace its casualties for as long as it took to create a unified, communist Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh—the aged, sickly, yet steadfastly popular revolutionary leader and president of North Vietnam, remained brazenly confident. “You will kill ten of us, we will kill one of you,” he said in response to American victories on the battlefield, “but in the end, you will tire of it first.”

—

IT WAS difficult to judge whether or not the North Vietnamese people were tiring of the killing. Nearly 200,000 of their own people had been lost, but North Vietnam had no freedom of speech or press; all distributed information was censored. U.S. Psychological Operations dropped millions of leaflets over the north, informing the populace of the massive defeats and body counts in the south, telling them that their Uncle Ho was sending them to slaughter. Still, voluntarily or not, they came, as Ho promised they would.

A key American strategy to bringing eventual peace to the south was to deny the North Vietnamese access to the “battlefield” by closing off enemy ingress at the borders. By the time Roy earned his green beret, the combined branches of the American military working with their ARVN allies had effectively limited the communists’ ability to send war matériel and replacement troops into South Vietnam via both the demarcation line between north and south (the 17th parallel) and the entire eastern coastline of the South China Sea, which wraps around the southern tip of South Vietnam and into the Gulf of Thailand.

The western border of South Vietnam, on the other hand, was abutted by the countries of Laos and Cambodia, whose representatives had signed legal declarations of neutrality during the 1954 Geneva Peace Conference, which prohibited them from joining any foreign military alliance. Nor could they allow the operations or basing of foreign military forces to occur on their territories. Representatives from the Associated State of Vietnam (the predecessor of the Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam), the People’s Republic of China, the Soviet Union, France, Great Britain, and the United States had also signed the document, acknowledging that their countries would adhere to and respect the stated rules.

But, like water from a leaking dam, tons of communist war matériel and thousands of troops continued to flow steadily from North Vietnam, through sections of Laos and Cambodia and into the south—a direct violation of

the aforementioned declarations.

This communication and supply route was known by the United States as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and by the north as the Truong Son Strategic Supply Route. The word trail had become a misnomer by 1967, since it had evolved from a centuries-old smugglers’ pathway, hacked out of the jungle and only wide enough for a person pushing a bike or a small cart, to thousands of miles of interconnected footpaths, waterways, and in places, multilane roads. The route was built, camouflaged, repaired, and maintained by Group 559, a transportation and logistical unit of NVA men, women, and children, whose sole purpose was to keep it passable.

The trail began in North Vietnam and entered directly into Laos, allowing the enemy to bypass American and South Vietnamese defenses at the line of demarcation. It then continued southward for more than a thousand miles: a vast and geographically treacherous journey through steep mountains, jungle, and swamps inhabited by tigers, poisonous insects, snakes, and malaria-carrying mosquitoes. At various points along the way, branches ran east as infiltration routes into South Vietnam.

The trail advanced roughly two hundred to three hundred miles south through Laos before entering Cambodia, where it paralleled the eastern border for another seven hundred miles all the way down to the Gulf of Thailand and the Cambodian seaport of Sihanoukville. Communist troops used this pipeline to stage and launch offensive operations into South Vietnam, then retreat and regroup inside the Laotian or Cambodian jungle sanctuaries that U.S. air and ground forces were not permitted to enter.

Cambodia’s leader, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, publicly and adamantly denied that North Vietnam was using his country militarily. Intelligence gathered by the United States, however, suggested that Sihanouk both knew of and was profiting from the arrangement, selling rice by the ton to the North Vietnamese, who rationed out 700 grams (three cups) per day to trail builders, porters, and troops in transit to the battlefields of the south. The general wartime allotment per person per day in their home villages in North Vietnam was around 450 grams (two cups), making it a lucrative black market business.

Sihanouk also permitted communist ships from both China and the Soviet Union to dock at the Sihanoukville seaport and off-load into warehouses. At night, covered Russian trucks—their headlights off—departed the warehouses and headed north. This suspected northbound transportation system for supplies was referred to by U.S. intelligence as the Sihanouk Trail, or Sihanouk Road, which merged into the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

—

JUST AS the North Vietnamese and Prince Sihanouk staunchly denied the existence of communist bases and supply lines within Cambodia, so too did President Johnson deny the presence of U.S. troops in that country. “We are in Vietnam to fulfill a solemn promise,” he said regularly during television and radio addresses. “We are NOT in Cambodia.”

Covertly, however, LBJ had begun to authorize small-scale reconnaissance missions into Cambodia as early as April 1967, albeit with a laundry list of restrictions. These highly classified operations were conducted under the guise of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG), whose mission on paper was to “study and observe” U.S. military operations. The name deliberately evoked a think tank of analysts or statisticians holed up in a reinforced Saigon basement and removed from the action.

In fact, very few high-ranking officers in the U.S. military and intelligence communities were even aware of the existence of SOG, the Studies and Observations Group, and fewer still were privy to its ultra-secret, anticommunist, counterinsurgency mission. In 1967, the commander of SOG was Colonel Jack Singlaub, a hard-charging Special Operations veteran who had conducted covert ops behind enemy lines in both World War II and Korea. As chief of SOG, Singlaub reported directly to General Ray Peers—the special assistant for counterinsurgency and special activities as well as the conduit to the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon. “General Westmoreland had the authority to veto our operations,” says Singlaub, “but we had to get approval from the White House and the Commander in Chief Pacific Command Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp. It was a very short list of people; we were well shielded. I don’t believe I was ever asked to be interviewed by a reporter while I was in Saigon. Who wants to interview the Studies guy?”

For the first two-plus years of its existence SOG had focused on Laos and North Vietnam, but when LBJ finally authorized cross-border reconnaissance (recon) teams to operate deep in Cambodia, “the intelligence was alarming,” Singlaub says. “The number of communist troops, NVA and VC, the bases, and hospitals, R & R centers, it was alarming, and it was frustrating. Especially at first, before we could take the fight to the enemy.”

Westmoreland and his conventional U.S. and ARVN forces, both air and ground, were champing at the bit to go after Charlie in his Cambodian lair. But without the green light to cross over the border en masse, the best they could do was stretch their leashes across the rarely marked and always rugged boundary. The NVA/VC became infamous for hit-and-run-for-sanctuary tactics. But what about the grunt whose buddy just got shot through the neck? Does he stop chasing his ambusher at the border or does he push the limits for payback?

Skirmishes between U.S. and ARVN troops and communists retreating over the border were inevitable, and when Cambodians were caught in the cross fire, Prince Sihanouk was quick to denounce U.S. and South Vietnamese “acts of aggression.” He made his stance clear as far back as May 3, 1965, by closing the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, thus ending diplomatic relations with the United States. In a public radio broadcast, Sihanouk explained that this was retaliation “for an April 28 bombing-strafing attack by four South Vietnamese planes against two Cambodian border villages in which one person had been killed and three wounded,” reported Newsweek on May 5. “Recalling his previous warnings that Cambodia would sever diplomatic ties with Washington if another Cambodian were killed in a Vietnam border incident, [Sihanouk said] ‘Our warnings were not heeded.’ ”

There was speculation that Sihanouk’s motivation for closing the embassy wasn’t retribution, but instead was a means to deny the Americans a way station for spies—a diplomatic perch from which to watch over the prince as he provided for and plotted with the Soviets, Chinese, and North Vietnamese. The Johnson administration, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and CIA were all but certain that the communists had his ear while their guerrillas and soldiers had his jungle, his rice, his roads, his sanctuary.

“Once it was done, and the last of the U.S. Embassy personnel had packed their bags and left, taking their radio transmitters and other espionage equipment with them,” Sihanouk wrote in his memoir, published seven years later in 1972. “I felt as if an enormous weight had rolled off my shoulders.”

While the politicians bantered back and forth and pointed their fingers, and journalists clamored for the next big story on the war, never once was the Studies and Observation Group outed by its members, who stealthily roamed around enemy encampments, performed their reconnaissance duties, rescued downed pilots, raided prisoner-of-war (POW) camps, and killed quite a few North Vietnamese and VC along the way. There were no newspaper headlines, television special reports, books, memoirs, or magazine articles published in the weeks, months, even years after the war ended that exposed what SOG was about. How small teams of two or three American Special Operations warriors—predominantly Green Berets, but also Navy SEALs, Force Recon Marines, and Army Rangers—and three or four indigenous mercenaries would sneak over the border to harass the enemy, reconnoiter his sanctuaries, and provide accurate intelligence regarding his bases, weapons, numbers, and plans. The cloak of secrecy was so effective that nearly all the men recruited or assigned to SOG had never heard of it or its mission beforehand. On rare occasions, a SOG warrior leaked its existence—but only to exceptional fellow warriors, whom he respected and felt would fit in.

—

IN THE last week of October 1967, twenty-one-year-old Special Forces Communications Sp

ecialist 4 Brian O’Connor stood before “the big map” inside the assignment office at 5th Special Forces Group headquarters, Nha Trang, Vietnam. Bristling from the wall-size rendition of South Vietnam were eighty-four pushpins bearing different-colored flags to represent the Special Forces A-team and B-team camps and bases dotting the countryside. Fifth Group headquarters, the C-team, was on the central east coast with a big “you are here” arrow pointing at it.

A sergeant major explained to O’Connor how each flag had a dash, a dot, or an X—a symbol of some sort—penciled on it, representing the personnel needs of that particular team or detachment: weapons specialist, medic, operations and intelligence, engineer. If there had been a symbol for commo, O’Connor’s MOS, on the company HQ flag, he could have stayed right there at headquarters in Nha Trang, where Vietnamese girls at the mini-PX shop around the corner sold ice-cream cones for ten cents apiece. Instead, he requested to go to the team called B-56.

The sergeant major hesitated and then pointed to the flag numbered “61” northeast of Saigon. “B-56 is at Ho Ngoc Tao,” he told O’Connor. “Do you know anybody there?”

As a kid, O’Connor had learned Morse code in Boy Scouts, and along with his father—who worked on top secret radio and electronics development projects during World War II—built several radios out of bits and pieces they found around the house: cardboard tubes, wires, and the key ingredient, a galena crystal (a piece of rock used as a semiconductor to recover audio from radio frequency waves). He’d even set up an illegal FM radio station one summer with some buddies, prompting the legitimate radio stations to contact the Feds, who quickly shut it down.

Legend

Legend The Last Season

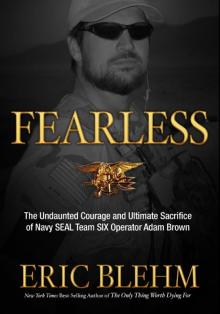

The Last Season Fearless

Fearless The Only Thing Worth Dying For

The Only Thing Worth Dying For